Cognitive Load Theory Might Be The Most Important Thing A Teacher Should Know

by Terry Heick

What is the most important thing a teacher should know?

According to British educationalist Dylan Wiliam, it is the Cognitive Load Theory (Wiliam 2017). Is it true? Well, that depends. First some backstory.

As we discussed in The Definition Of The Cognitive Load Theory: A Definition For Teachers, The Cognitive Load Theory is a learning theory that seeks to clarify the limitations of the human brain so that instruction can be designed to mitigate these ‘weaknesses’ and result in improved learning outcomes (learning more, learning more deeply, etc.)

The New South Wales Department of Education recently released a paper that explores the Cognitive Load Theory in great detail. Their definition of the Cognitive Load Theory (I have chosen to capitalize its label for formatting purposes):

‘Cognitive load theory is based on a number of widely accepted theories about how human brains process and store information (Gerjets, Scheiter & Cierniak 2009, p. 44). These assumptions include: that human memory can be divided into working memory and long-term memory; that information is stored in the long-term memory in the form of schemas; and that processing new information results in ‘cognitive load’ on working memory which can affect learning outcomes (Anderson 1977; Atkinson & Shiffrin 1968; Baddeley 1983).’

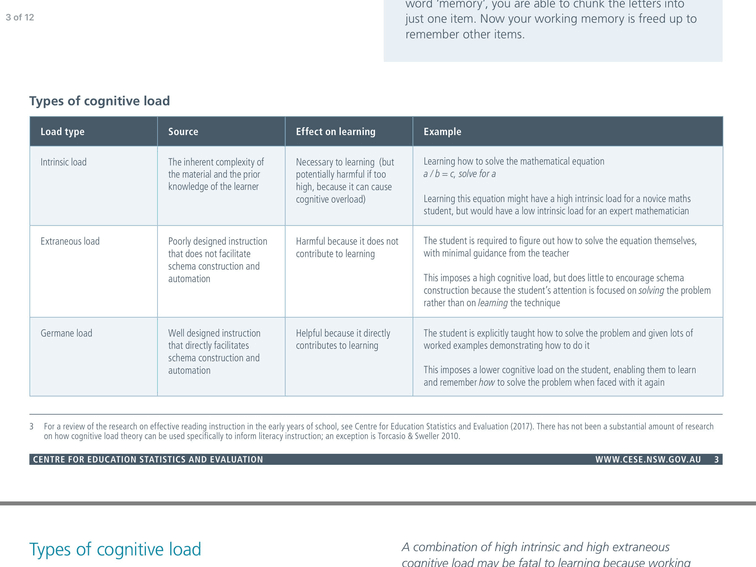

Further, Sweller’s theory separates this concept of ‘cognitive load’ into three categories: intrinsic, extraneous, and germane. (I’ll write about the levels and their implications separately.)

Why The Cognitive Load Theory Is A Big Deal

As explained, the Cognitive Load Theory, designed in 1988 by John Sweller at the School of Education, University of New South Wales, is based on the limitations of the human brain.

Because our short-term memory is severely limited and because of this, teachers should be clear about both task sequence and the ‘design’ of task complexity. If the complexity isn’t a direct cause or effect of the mastery of the learning objective, the task should be modified.

This makes sense. If you’re asking a student to think critically about a concept that they’re only beginning to grasp, at best the critical thinking ability would be limited and, at worst, very little learning would occur at all. If you ask a student to–directly or indirectly–apply problem-solving skills to a project where they are learning (new information) about how DNA drives evolution or how different forms of government work, you’re two things poorly:

1. Asking the brain to do two things at once, which sounds ‘real-world,’ but is bad in the ‘real-world’ too. This limits both processes. The task is ‘complex,’ but not in a way that benefits the student.

2. Putting the cart before the horse. As a matter of instructional design, you’ve got the sequence all wrong. Acquire domain-specific knowledge, says the theory, and then use it in new and novel ways.

In that way, the Cognitive Load Theory seeks to make learning more efficient through instructional design. If learning experiences are designed in awareness of using ‘cognitive load’ intentionally and strategically, the theory suggests that learning outcomes will be improved.

(If you’re interested, you can read Sweller’s original study/paper here.)

Is This The Most Important Thing Any Teacher Should Know?

Of course, this has significant implications for how teachers might design lessons, units, and assessments, and for how curriculum developers use instructional design elements that brain-based learning.

While what ‘the most important thing every teacher should know’ is entirely relative and subjective and seems sensationalizing to even discuss, imagine not understanding that you have to walk before you can crawl.

Imagine insisting that students grapple with complexity through authentic project-based learning and classic literature and essay-writing and ‘rigorous’ and highly-academic tasks–all celebrated in modern education circles–without realizing that you’re overloading their short-term memory–that you’re more or less making sure they actually ‘learn’ very little by design.

That instead of using the schema that they do have to create some new knowledge, piece by piece, helping them understand the utility of each new morsel of understanding as you go–instead of that, because you’re hell-bent on ‘rigor,’ you’re instead the architect of their struggle and confusion.

They spend the bulk of the learning you’ve planned trying to decode the assignment, extrapolating from your tone and body language what’s most important for them to do to get your approval and a good grade while their brain ends up processing processing processing, going back and forth between short-term right now and long-term this is what I know to make sense of everything that’s happening.

Ugh.

Imagine trying to teach a child to run without first teaching them to crawl, then toddle, then jog. That’d be a major problem. Even if you could come up with ways for them to leap right past crawling to sprint, at what cost? And how accurately can one teacher be expected to know what ‘sprinting’ looks like for every child? In response, we generalize–we create general circumstances to learn within and artificially narrow ways to demonstrate learning, never reconciling the two.

Imagine, instead of showing someone what a tree is and then how to cut a tree down and process it for lumber and then how to design a house and how to fasten one plank of lumber with another and so on–imagine instead of doing that, you instead talked about real estate patterns and trends in modern architecture?

Or in the first unit you worked on roof pitch and gable design and exterior paint, and in the second unit you looked at stairs and floors and the third foundation building and the fourth blueprint design. That’d be weird, right?

Of course, it’s not that simple for teachers because every content area is different and academic standards are different. Not all would suggest a ‘baby steps’ sequence like I’ve visualized above. But while these analogies are not perfectly accurate, they hopefully hit at the same big idea: instructional design really, really matters and is often left out of the hands of teachers.

In the short run, it enables poorly-designed learning for students, and in the long run, reduces teacher capacity for instructional design, making it an afterthought–a matter of planning to be considered in the context of everything else instead of before everything else.

So while relationships building and classroom management and organization and lesson planning and assessment design and dozens of other competencies are crucial to teaching, the ability to parse content into usable blocks that can be built (alongside students) into a compelling ‘wholes’ might be the most important thing a teacher can know how to do.

Every student is different–different curiosities, different background knowledge sets, different reading levels, different levels of tolerance for a noisy classroom or a disorganized teacher and on and on. Rarely is curriculum designed to respond to these realities. Learning frameworks and assessment models, too, usually fail to honor the need for personalization in learning.

In a class of 28 students, if the teacher doesn’t create 28 individuals bridges between the content and the student, who will?

The Cognitive Load Theory: What Teachers Should Know