Grant Wiggins’ Lasting Lessons For Teachers

by Jay McTighe

Ed note: If you’re interested in hearing a (podcast) conversation between Jay McTighe and Grant’s wife, Denise Wilbur, along with ASCD Faculty member Donnell Gregory, head over to ASCD.

The start of the new school year offers the perfect opportunity to reflect on the life and work of Grant Wiggins, an extraordinary educator who died unexpectedly at the end of the last school year (on May 26, 2015). Although I am an only child, I considered Grant my brother as well as an intellectual partner and best friend. I think of Grant every day and miss him terribly.

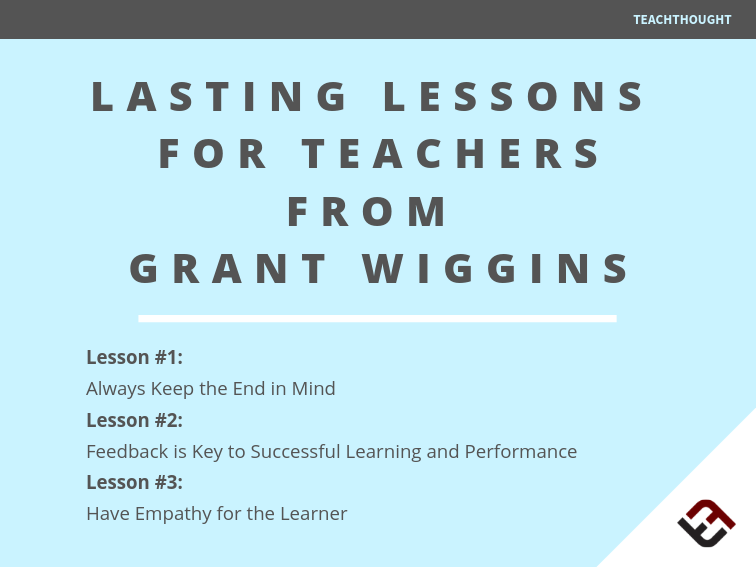

While Grant is no longer with us, his spirit and ideas live on. Indeed, we can honor and celebrate his life’s work by acting on the sage advice that he offered to teachers over the years. As we prepare to meet our new students, let us consider three of Grant’s sensible and salient lessons for teachers.

What Grant Would Want You To Know

Lesson #1: Always Keep the End in Mind

Grant always reminded teachers of the value of designing curriculum, assessment, and learning experiences “backwards,” with the end in mind. While the idea of using “backward design” to plan curriculum units and courses is certainly not new, the Understanding by Design® framework underscores the value of this process for yielding more clearly defined goals, more appropriate assessments, more tightly aligned lessons, and more purposeful teaching.

Grant pointed out that “backward design” of curriculum means more than simply looking at all of the content and standards you plan to “cover” and mapping out your day-to-day lessons. The idea is to plan backward from worthy goals—the transferable concepts, principles, processes, and questions that enable students to apply their learning in meaningful and authentic ways. Grant knew that in order to transfer their learning, students need to understand “big ideas.” Rote learning of discrete facts and skills will simply not equip students to apply their learning to novel situations. Thus, he advised teachers to plan backward from desired transfer performances and “uncover” the necessary content needed for those performances.

Here are several curriculum-planning tips that Grant offered:

- Consider long-term transfer goals when planning curriculum. What do you want students to be able to do with their learning when they confront new challenges, both within and outside of school?

- With transfer goals in mind, ask yourself these questions: What will students need to understand in order to apply their learning? What specific knowledge and skills will enable effective performance?

- Frame your teaching around essential questions. Think of the content you teach as the “answers.” What are the questions that led to those answers?

Grant noted that teaching for understanding and transfer will develop the very capabilities identified in the Common Core State Standards and Next Generation Science Standards, which are necessary to prepare learners for success in college and careers.

Lesson #2: Feedback is Key to Successful Learning and Performance

However, Grant cautioned against thinking that grades (B+) and exhortations (“try harder”) are feedback.

To be effective, Grant pointed out that feedback must meet several criteria:For years, Grant reminded teachers that providing learners with feedback was a key to effective learning and improvement. His insights have been confirmed by research (from educators like Dylan Wiliam, John Hattie, and Robert Marzano) that demonstrates conclusively that classroom feedback is one of the highest-yielding strategies to enhance achievement.

- Feedback must be timely. Making students wait two weeks or more to find out how they did on a test will not help their learning.

- Feedback must be specific and descriptive. Effective feedback highlights explicit strengths and weaknesses (e.g., “Your speech was well-organized and interesting to the audience. However, you were speaking too fast in the beginning and did not make eye contact with the audience.”).

- Feedback must be understandable to the receiver. Sometimes a teacher’s comment or the language in a rubric is lost on a student. Using student-friendly language can make feedback clearer and more comprehensible. For instance, instead of saying, “Document your reasoning process,” a teacher could say, “Show your work in a step-by-step manner so others can follow your thinking.”

- Feedback must allow for self-adjustment on the student’s part. Merely providing timely and specific feedback is insufficient; teachers must also give students the opportunity to use it to revise their thinking or performance.

Here’s a straightforward test for classroom feedback: Can learners tell specifically from the given feedback what they have done well and what they could do next time to improve? If not, then the feedback is not yet specific enough or understandable for the learner.

Grant also reminded us that classroom feedback should work reciprocally—that is, teachers should not only provide feedback for learners but also seek and use feedback to improve their own practice. Here are four ways that teachers can obtain helpful feedback:

- Ask your students. Periodically, teachers can elicit student feedback using “exit cards” or questionnaires. Here are a few sample prompts: What do you really understand about ____? What questions do you have? When were you most engaged? When were you least engaged? What is working for you? What could I do to help you learn better? Response patterns from such questions can provide specific ideas to help teachers refine their teaching.

- Ask your colleagues. It is easy for busy teachers to get too close to their work. Having another set of eyes can be invaluable. You can ask fellow teachers to review your unit plans, inspect the alignment of your assessments to your goals, and check your essential questions and lesson plans to see if they are likely to engage students

- Use formative assessments and act on their results. Grant often used analogies to make a point. He likened formative assessment to tasting a meal while cooking it. Waiting until a unit test or final exam to discover that some students haven’t “got it” is too late. Effective teachers, like successful cooks, sample learning along the way through formative assessments and adjust the “ingredients” of their teaching based on results.

- Regularly analyze student work. By closely examining the work that students produce on major assignments and assessments, teachers gain valuable insight into student strengths as well as skill deficiencies and misunderstandings. Grant encouraged teachers to analyze student work in teams, whenever possible. Just as football coaches review game film together and then plan next week’s practices, teachers gain insight into needed curriculum and instructional adjustments based on results.

For more reading, here is Grant on providing better feedback for learning.

Lesson #3: Have Empathy for the Learner

In our writings on Understanding by Design, Grant and I described six facets of understanding: a person shows evidence of understanding when they can explain, interpret, apply, shift perspective, empathize, and self-assess. These facets serve as indicators of understanding and guide the development of assessments and learning experiences.

Grant pointed out that the facets have value beyond their use as a frame for curriculum and assessment design. They can be applied to teachers and teaching as well. As one example, he described the phenomenon that he labeled the Expert Blind Spot: “Expressed in the language of the six facets, experts frequently find it difficult to have empathy for the novice, even when they try. That’s why teaching is hard, especially for the expert in the field who is a novice teacher. Expressed positively, we must strive unendingly to be empathetic to the learner’s conceptual struggles if we are to succeed.”

Grant reminded us of the value of being sensitive to learners who do not have our expertise (and sometimes not even an interest) in the subject matter that we know so well. He pointed out that “what is obvious to us is rarely obvious to a novice—and was once not obvious to us either, but we have forgotten our former views and struggles.” He cautioned us against confusing teaching for understanding with simply telling. He encouraged teachers to remember that understandings are constructed in the mind of the learner, that understanding must be “earned” by the learner, and that the teacher’s job is to facilitate “meaning making,” not simply present information.

Grant encouraged teachers to develop empathy for students by “shadowing” a student for a day and reflecting on the experience. Recently, a high school teacher took his suggestion and described what it was like to walk in the shoes of a student. Her account, summarized in a blog post with over a million hits, should be required reading for all teachers, especially at the start of a new year. Maybe you will be inspired to engage in this action research in your school.

These are but a few of the many lessons that Grant offered us. Although he is no longer with us, his brilliance lives on in his thought-provoking blog posts, articles, and books. His advice elevates our profession, and our students deserve the benefits of his wisdom.

Jay McTighe leads ASCD’s Understanding by Design® cadre and brings a wealth of experience that he developed during a rich and varied career in education. He served as director of the Maryland Assessment Consortium, a state collaboration of school districts working together to develop and share formative performance assessments. McTighe is an accomplished author, having coauthored 14 books, including the best-selling Understanding by Design series with Grant Wiggins.

This post originally appeared on ASCD’s Inservice blog; image attribution flickr user sparkfunelectronics