The Activity Learning Theory: An Overview

contributed by Steve Wheeler, Associate Professor, Plymouth Institute of Education

This is number 8 in my series on learning theories. My intention is to work through the alphabet of psychologists and provide a brief overview of each theory, and how it can be applied in education. In the last post we examined the various educational theories of John Dewey including experiential learning.

In this post, we explore the work of Yrjö Engeström on Activity Theory. This is a simplified interpretation of the theory, so if you wish to learn more, please refer to the original work of the theorist. Activity Theory (AT) originated in Soviet Russia from the work of Vygotsky and Leont’ev on Cultural Historical psychology and Rubenstein and others on related neuropsychological perspectives.

It is a complex theory which draws on a number of disciplines and it has far reaching implications for education. The Scandinavian school of thought that has developed around Activity Theory is arguably the most referred to in the literature and is largely based on the work of Yrjö Engeström.

How The Activity Learning Theory Works

Vygotsky’s earlier concept of mediation, which encompassed learning alongside others (Zone of Proximal Development) and through interaction with artifacts, was the basis for Engeström’s version of Activity Theory (known as Scandinavian Activity Theory). Engeström’s approach was to explain human thought processes not simply on the basis of the individual, but in the wider context of the individual’s interactions within the social world through artifacts, and specifically in situations where activities were being produced.

In Activity Theory people (actors) use external tools (e.g. hammer, computer, car) and internal tools (e.g. plans, cognitive maps) to achieve their goals. In the social world there are many artifacts, which are seen not only as objects, but also as things that are embedded within culture, with the result that every object has cultural and/or social significance.

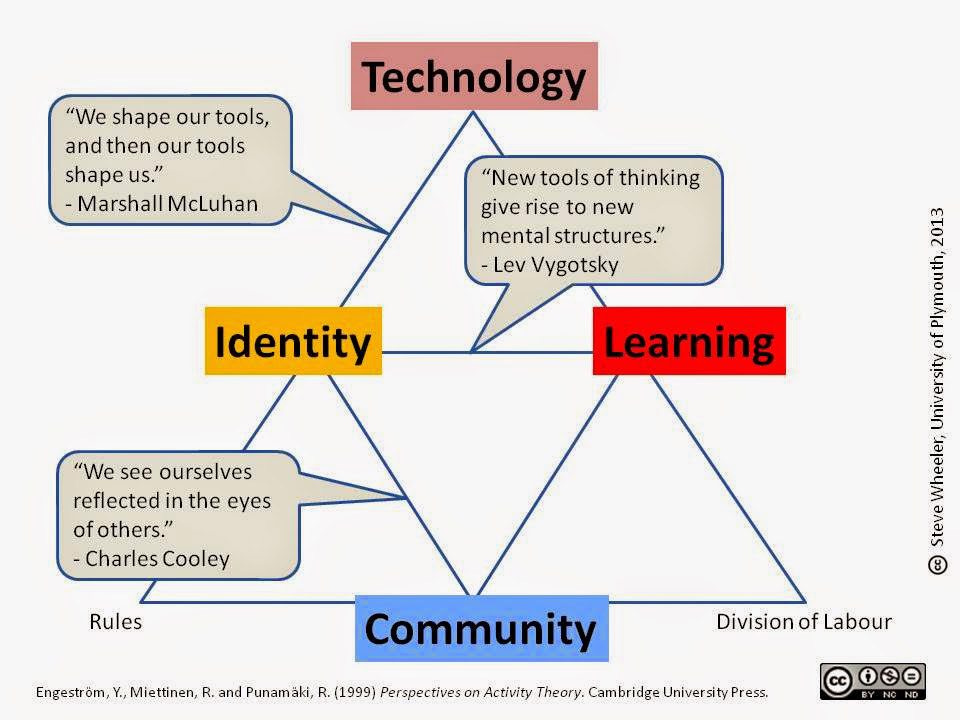

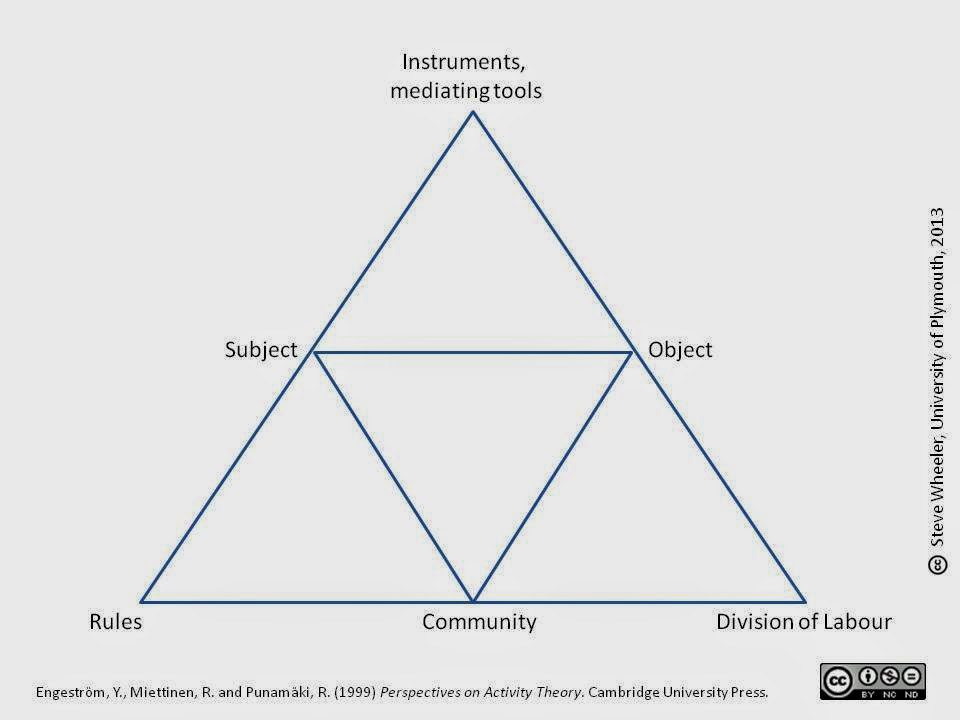

Tools (which can limit or enable) can also be brought to bear on the mediation of social interaction, and they influence both the behavior of the actors (those who use the tools) and also the social structure within which the actors exist (the environment, tools, artifacts). For further reading, here is Engeström’s own overview of 3 Generations of Activity Theory development. The first figure shows Second Generation AT as it is usually presented in the literature.

The first figure is my interpretation in relation to digital presence, community and identity, while the latter is based on Engeström’s work.

How It Can Be Applied In Education

Teachers should be aware that everything in the classroom has a cultural and social meaning. The way children interact with each other and with the teacher will be mediated (influenced) by objects such as the whiteboard, furniture, technology, and even the shape, size and configuration of the room. This also includes its ambient characteristics such as lighting and noise levels. Learning occurs within these contexts, and usually through specific activities.

Teachers should ensure that those activities are relevant and iterative, providing students with incremental challenges that they can engage with at a social level, so that the entire community of learners extends its collective knowledge through the construction of meaning. Teachers should also be aware that tools can limit as well as enable social interaction, so must be applied wisely and appropriately to promote the most effective learning.

Reference

Engeström, Y., Mietinnen, R. and Punamäki, R-L. (Eds: 1999) Perspectives on Activity Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Previous posts in this series:

Anderson ACT-R Cognitive Architecture

Argyris Double Loop Learning

Bandura Social Learning Theory

Bruner Scaffolding Theory

Craik and Lockhart Levels of Processing

Csíkszentmihályi Flow Theory

Dewey Experiential Learning

This post first appeared on Steve’s personal blog; How The Activity Learning Theory Works; Graphic by Steve Wheeler