How To Use Flexible Grouping In The Classroom

Having students interact with one or more peers can build community, increase engagement, and make learning more active.

How Can You Use Flexible Grouping In The Classroom?

contributed by Jessica Hockett, PhD., and Kristina Doubet, PhD

Groups and group work are woven into the fabric of many classrooms.

Having students interact with one or more peers can build community, increase engagement, and make learning more active. But deciding whether and how best to form groups can daunting.

Because grouping can be challenging and complex, many teachers either avoid using groups altogether or keep students in the same groups. This practice of ‘static grouping’ keeps students in the same groups for weeks or months at a time. They don’t ‘switch up’ often according to task purpose and assessment evidence. This can rob students of opportunities to learn from—and develop relationships with—all of their peers.

Flexible grouping, by contrast, organizes students intentionally and fluidly for different learning experiences over a relatively short timeframe (e.g., two weeks). Groupings are well-matched to task purpose and fueled by classroom assessment results and other student characteristics.

See also The Difference Between Synchronous And Asynchronous Learning

The Benefits Of Flexible Grouping

Practiced well, flexible grouping has three benefits over static grouping.

1. Flexible grouping brings students together.

Any time students work in a small group they are separated from the rest of their classmates. With flexible grouping, separation is temporary. Over the course of days, weeks, and months, students come together to work with a wide range of peers in new ways prevented by continuous whole-group work, independent work, or interaction in a static small group. Flexible grouping strengthens rather than threatens classroom camaraderie.

2. Flexible grouping exposes students to new and divergent perspectives.

Like adults, children of all ages gravitate toward people who are like them–who share their points of view, have similar experiences and interests, and seem to value the same things. Wanting to stick with friends is normal, and sometimes helpful. But students can also get too comfortable or stuck in a rut working with the same peers day in and day out. Flexible grouping pushes them out of their comfort zones and into interactions with peers they might not otherwise choose or get a chance to learn from.

3. Flexible grouping combats status differences.

Teachers’ grouping decisions send powerful messages to students about their roles in and value to the classroom community. When they are put into a group, most students “size up” the learning situation (Who’s in my group? Who’s in that group? What are we doing? What are they doing?).

They are conducting a kind of status check, gathering clues about what the teacher believes about their abilities. Flexible grouping makes it difficult for students to pigeonhole one another (or themselves). Groups are sometimes based on students’ readiness or skill level, but they are interspersed with groupings based on interest, learning preference, experience, etc.

Planning for Flexible Grouping

Planning for flexible grouping isn’t difficult or time-consuming, but it does take some thought.

Should students stay in whole group or work in partners? Is it better if they read alone or in a trio? Are groups of four too big or too small for a Jigsaw? Can students choose their own teams, or should the teacher? Does skill level matter most for the group task, or interest?

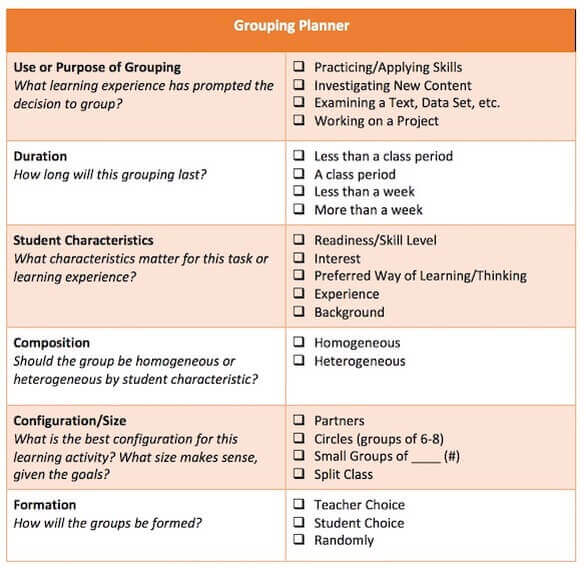

This Grouping Planner shows the factors a teacher weighs in the decision-making process.

Thinking About Flexible Grouping

When planning flexible grouping, among the first considerations are purpose and duration: what students will be doing in the group, why they will be doing it, and for how long? Will students be practicing or applying a skill? Exploring new content or ideas? Analyzing a poem or data from a survey? Working on a short- or long-term project? Whatever the “reason,” it should be a good fit for group work–that is, a task better-accomplished with others, rather than independently.

Equally important to consider are student characteristics and group composition. What patterns of traits ‘matter’ for the particular task? Are students in different places in their mastery of a certain skill (e.g., reading complex text, solving equations, or conducting experiments)? If so, it makes sense to place students in groups of like-readiness and give each group work that targets their particular areas of strength or weakness.

Does the lesson topic need more ‘spice’? Perhaps placing students in groups of similar interest to explore the topic through that ‘lens’ will increase motivation. Following their initial exploration, students could get into groups of mixed interest to explore the topic in more breadth. Students’ preferences for accessing content (e.g., reading about it, watching a video about it) can serve as another way to form homogeneous groups. Heterogeneous groups work well when a mixture of perspectives and backgrounds–genders, beliefs, extra-curricular endeavors–is important.

The configuration or size of the group should be strongly tied to the purpose of the groups. Splitting the class into two groups might work for a class debate. Three or four circles of 6-8 students could be optimal for discussing short stories students have chosen by interest. For a Jigsaw task, smaller groups of 3-4 may work best. A lab that has been differentiated for readiness could be best-suited to partners.

Another consideration is who or what will actually form the groups. In one sense, the teacher is always in control of the formation, even if he or she decides to let students choose their own groups, or to let ‘random’ criteria (e.g., birthday month, height) decide. While task purpose and student characteristics should be at the forefront of decision-making, for flexible grouping to actually occur, teachers must keep a close eye on configurations over time. Over the course of several weeks, students should have opportunities to work in a variety of groups with a range of peers.

Laying a Foundation for Flexible Grouping

Of course, simply plopping students next to a variety of partners every week doesn’t automatically create close or instant bonds. The teacher must take deliberate steps to prepare students to work interdependently with classmates whom they may or may not consider ‘friends.’

To set the tone for flexible grouping, let students know at the year’s outset that they will be switching groups frequently. Then, begin using a wide variety of ‘random’ groupings for brief activities like Think-Pair-Share, brainstorming, or responding to a question or prompt.

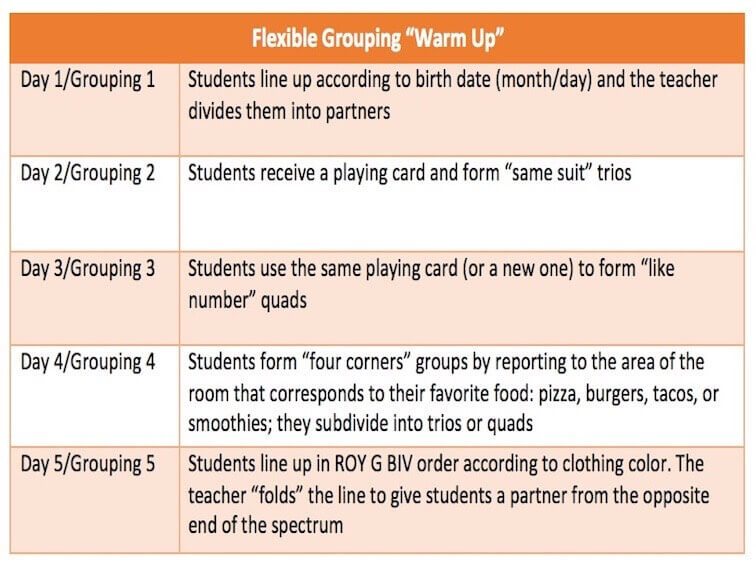

Here’s one example that can be implemented five days in a row—or for five days over a two-week period.

Flexible Grouping “Warm Up”

Day 1/Grouping 1: Students line up according to birth date (month/day) and the teacher divides them into partners

Day 2/Grouping 2: Students receive a playing card and form “same suit” trios

Day 3/Grouping 3: Students use the same playing card (or a new one) to form “like number” quads

Day 4/Grouping 4: Students form “four corners” groups by reporting to the area of the room that corresponds to their favorite food: pizza, burgers, tacos, or smoothies; they subdivide into trios or quads

Day 5/Grouping 5: Students line up in ROY G BIV order according to clothing color. The teacher “folds” the line to give students a partner from the opposite end of the spectrum. This sets the expectation and tone for flexible grouping by getting students used to moving around and working with different peers.

As students become accustomed to this constant state of flux, they worry less about who is in their group and why. Their focus shifts to what they are supposed to accomplish in their groups and how best to do so.

Conclusion

Ideally, flexible grouping creates an environment where students are more collaborative, empathetic, and more willing to take risks – with the content and with one another. This sets the stage for their development as people, not just as students.

At its best, flexible grouping increases students’ capacity to behave as responsible, respectful, contributing citizens: something that will serve them well for years to come.