Knowledge Demands Change Faster Than Every Other Part Of Education

Give me a curriculum based on people–based on their habits and thinking patterns in their native places and a genuine need to understand.

This post has been updated from its original publication in 2016

Stop Teaching Classes And Start Teaching Children

Increasingly, the idea of computer coding is being pushed to the forefront of things.

In movies, on the news, and other digital avatars of ourselves, coders are increasingly here. In Hollywood, computer coders are characterized as aloof and spectacle geniuses in green army jackets who solve (narrative) problems in a kind of deus ex machina fashion.

Hack the mainframe, change the school grades, save prom, etc. In the news, they are painted as an eclectic mix of cutting-edge vigilante and binary terrorist, with secret documents, scary viral threats, and national security all a part of their tools and struggle. Combined with the recent positively torrid surge of priority digital technology plays in our daily lives, coding sits at an awkward intersection—misunderstood by most, but tangent to almost everything.

So we should totally teach it in schools, right?

Teaching Skills vs Teaching Content

Too often bits and pieces are tacked onto curriculum as yet another perfectly-reasonable-sounding-thing to teach.

Yet in the ecology of a school, they behave differently in the classroom where the rubber hits the road. I was taught basic computer coding in the 1980s in elementary school. It was forced out by a push for foreign languages, as I recall (or that’s what teachers told us), foreign languages recently pushed out themselves by ‘reading’ classes or other periods of academic remediation.

There is nothing wrong with changes in priority. In fact, this is a signal of awareness and reflection and vitality. But when education—as it tends to do—continues to take a content and skills-focused view of what to teach rather than how students learn, it’s always going to be a maddening game of what gets added in, and what gets taken out, with the loudest or most emotionally compelling voices usually winning.

To try to address this problem, let’s consider a more macro question: What is school? From the big picture down, it looks relatively simple.

Education is, more or less, a system of teaching and learning.

Teaching and learning are, more or less, concerned with knowledge.

And that knowledge can be broken down into two separate but connected parts: skills and content.

Skills are things students can ‘do’—procedural knowledge that yields the ability to do something. This could be revising an essay, solving a math problem, or decoding words to read.

Content can be thought of as a second kind of knowledge—a declarative knowledge that often makes up the face of a content area. In math, this might be the formula to calculate the area of a circle. In composition, it could be a writing strategy to form sound and compelling paragraphs. In history, it may refer to the geographic advantages of one country in a conflict versus another.

Should schools focus on content and skills, or should they focus on habits and thinking? Does that answer change as the culture its students come from does? And should it change faster or slower–ahead of the curve, or far enough behind for cautious perspective?

Whether or not schools should teach coding is a question that cannot responsibly be answered by itself. Against the backdrop of rapid technological change, mass cultural adoption of technology, and the mediocre performance of our current education system, the question becomes just one of many that deserve our attention.

Without this kind of critique, coding will suffer alongside chemistry, music, and other miracles of knowledge that have had the life tortured out of them by a well-intentioned but brutal infrastructure. It will be halved, then halved again, diced, packaged, and served at room temperature day after day after day until no one remembers what they’re doing or why they’re there.

When Standards Aren’t Standards

Literacy has been at the heart of teaching and learning since the very beginning of, well, everything.

Not only is it a goal in and of itself, but it also is a prerequisite of other goals. Without the ability to read and write well, students struggle everywhere. But instead of placing reading and writing at the core of all content, as it functions, it is segmented into a class of its own, where teachers in the United States struggle with as many as five sets of Common Core Standards, each with dozens of standards.

Reading: Informational

Reading: Literature

Reading: Foundational

Writing

Speaking & Listening

Language

So then, hundreds of standards. Hundreds! This places extraordinary pressure on educators—those who develop standards, those who create curriculum from those standards, those who create lessons from that curriculum, and on and on—to make numerous—and critical—adjustments to curriculum, assessment, and instruction on the fly.

At some point, the word ‘standards’ has come to mean something different.

Imagine an over-worked kitchen struggling to make 130 versions of what people outside the kitchen recognize as the same sandwich. The influence of digital technology in our lives has forced education—already bursting at the seams with standards, assessment forms, data, mandated standards, accountability measures, instructional hours, and scores of other concerns–into the awkward position of believing it needs to fit in ‘more’ when it already struggles with less.

And in response, rather than rethink or even add to, we swap instead—foreign language and humanities for STEM, and, presumably, coding. Tomorrow, something else will get our attention that students ‘need to know’ that sounds important.

This reminds me of the Coen Brothers’ Raising Arizona. After hearing a long laundry list of things every baby needs from her friend Dot, Ed (Holly Hunter) turns to Hi (Nicholas Cage) in panic. The quick context is that they’re new parents who’ve just ‘adopted’ a baby and the stress of being a good parent is washing over them.

(You can watch the scene here.)

Ed (The new mom): Who’s our pediatrician anyway? We ain’t exactly fixed on one yet, have we Hi?

Hi (The new dad): *stunned silence*

Ed: No, I guess we don’t have one yet.

Dot: (The well-meaning-but-manic friend spreading her mania): What?! Well, you gotta have one this instant!

Hi: *stunned silence*

Ed: What if the baby gets sick, honey?

Dot: Even if he don’t, he’s gotta have his dip-tet.

Ed: He’s gotta have his dip-tet, honey.

Hi: *stunned silence*

Dot: You started his bank accounts yet?

Ed: Have we done that? We gotta do that. What’s that for, Dot? His orthodonture and his university!

Hi: *stunned silence, eyes like broken portals*

Changing Nature of Skills

Why not try a different approach–one that not only decenters curriculum but reimagines it completely?

Change causes uncertainty, and uncertainty can understandably cause insecurity and even panic. Take coding for example. Let’s say that one definition of digital literacy might be “the ability to interpret and design nuanced communication across digital forms.” Students need to be able to do this, yes?

Coding is just another collection of symbols. It’s the new reading and writing! And speak a foreign language too, right?

And paint and dance? Yes, yes.

And play an instrument and make things and manage projects through their own sustained inquiry and learn to be entrepreneurs?

Yes, yes, yes.

But a more apt question might be, how should schools—and the curriculum they seek to ‘deliver’—be reconsidered in light of prevailing local technologies and values?

What are people for, and how can schools help?

What is the relationship between a good school and good work and good living?

What’s worth knowing, how is that different for every person, and how might schools reconceive themselves in response?

How does a renewed global consciousness impact the ‘local’?

How does a connected planet change the kinds of things a person needs to understand? (It has to, right?)

Building A Curriculum-Based On People

In the past, we’ve sought to add-to and revise. Add these classes and drop these. This isn’t as important as this. To make knowledge an index that reflects the latest thinking that reflects our most recent insecurities and collective misunderstandings. This doesn’t seem like the smartest path to sustainable innovation in learning.

As the pace of change quickens through jolting connections, fresh priorities, and newly visible (and overlapping) inequities and opportunities, it’s time to rethink curriculum and its role in the learning process. In a fixed curriculum with set boundaries that is based on content, start with “Want to add coding? What are you willing to give up? Let’s trade.”

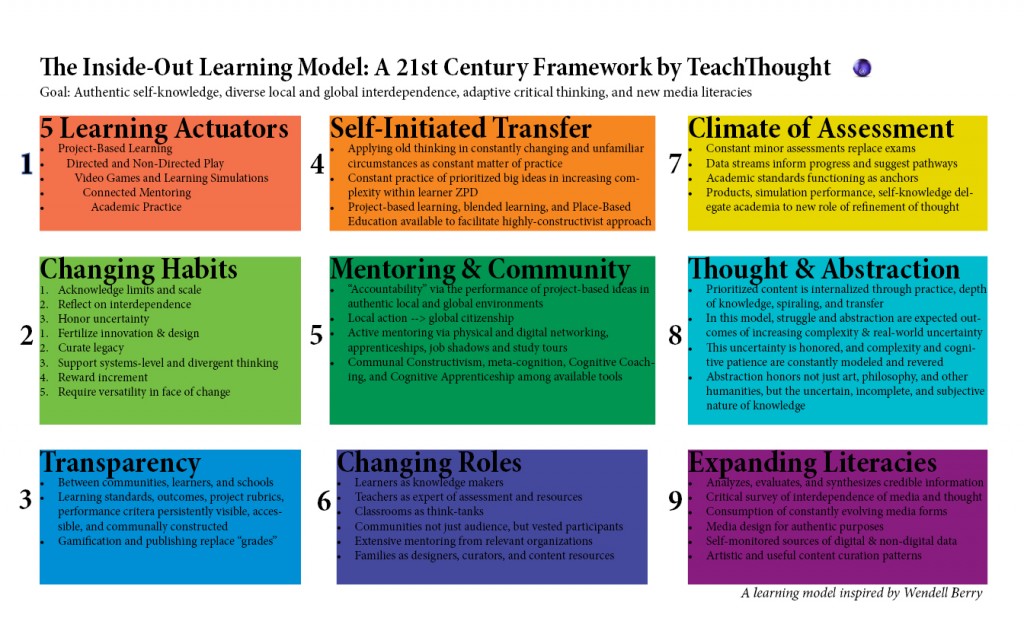

The idea of new skills and ideas being relevant in a changing world has been a core currency of ed debate since the 1990s (at least), manifesting as ’21st-century skills’ and ‘the 4 Cs,’ and so on. A few years ago, we created a graphic that helped to capture what a modern academic learning environment might look like. And an Inside-Out School. And two dozen other models we’ve developed trying to etch out–and then illuminate–how learning is changing, and what might be coming next.

It’s difficult to lead from behind, and schools have stayed far behind the curve, in part, by the core mechanic of their design–curriculum. They start with something slippery and opaque and subjective and endlessly problematic.

Content.

They take that content and package it as curriculum. They then study the ‘best practices’ of delivering that curriculum that yield the largest gains as measured by common assessments. A common curriculum and common assessments. They–or rather we–celebrate pie charts instead of people. The curriculum (and its mastery) is central. The schools and teachers and students are peripheral and entirely anonymous.

What if we took a different approach–something content-less and human-ful? Something fluid? In a fluid curriculum that’s based on something other than chronologically-sequenced opaque ‘understandings,’ there is new possibility–learning that’s not based on content and isn’t driven by teaching. In this case, it’s no longer restricted by either, so content and teachers can seek new roles.

Give me a curriculum based on people–based on their habits and thinking patterns in their native places. One that helps them see the utility of knowledge and the patterns of familial and social action. One that helps them ask, “What’s worth knowing, and what should I do with what I know?”

Then let’s work backward from that.

Shifting From A Curriculum Of Insecurity To A Curriculum Of Wisdom; image attribution flickr user susanfernandez; the handsome kid in the featured image is the author’s son