Are Students Struggling With Writing? The Data Suggests Yes

Ask almost any teacher whether students are struggling with writing and you’ll hear a quick yes. While complaints about “kids today” are nothing new, the current writing crisis is supported by more than sentiment. National assessments show persistent gaps in students’ ability to write clearly and coherently, and many schools and universities haven’t yet reversed these trends.

Below is a research-based overview of why literacy specialists, administrators, and policymakers are increasingly concerned about student writing—from elementary school through college and into the workplace.

1. Most students are not proficient writers.

Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Writing show that only a minority of students reach proficient levels in writing, and a substantial portion of 12th graders do not meet even basic standards. In other words, by the end of high school, many students still struggle with fundamental written communication.

2. Even with digital tools, only a small share can produce well-developed writing.

In NAEP’s most recent computer-based writing assessment, students composed their responses on computers and had access to spell-check and digital reference tools. According to the NAEP 2011 Writing Report , only about 27% of students produced essays rated as proficient or above. Students with regular access to computers at home tended to perform better, highlighting both digital literacy and opportunity gaps.

3. Over a quarter of college graduates write at a “deficient” level.

Employers consistently report that new graduates are not prepared for the writing demands of the workplace. In the employer survey “Are They Really Ready to Work?” (The Conference Board, Partnership for 21st Century Skills, and others), 26.2% of college graduates were rated as deficient in writing. Nearly 28% struggled with all forms of written communication, including emails, reports, and everyday workplace documents.

4. Many college students don’t feel their writing improves during college.

The longitudinal study Academically Adrift (Arum & Roksa) followed students across four years of college. Fewer than half of the seniors surveyed reported that their writing skills had substantially improved. The largest gains occurred among students in reading- and writing-intensive courses, suggesting that rigorous expectations and sustained practice are key to growth.

5. A significant share of freshmen need remedial writing—and it’s expensive.

Many students arrive at college without the writing skills expected for entry-level coursework. Analyses from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) show that a substantial percentage of first-year students enroll in remedial or developmental writing. These courses reteach high school content and contribute to billions of dollars in additional instructional costs for states and institutions.

The National Commission on Writing estimated that poor writing skills cost U.S. businesses more than $3.1 billion per year in remedial training. State governments spend hundreds of millions more to bring employees’ writing up to acceptable levels.

6. Persistent reading gaps compound writing problems.

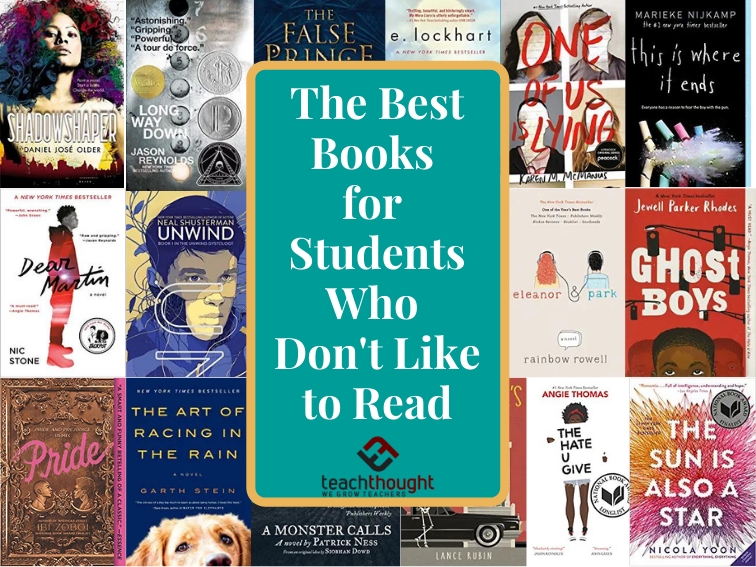

Reading and writing are tightly linked: students who read more widely and frequently tend to write with greater fluency, vocabulary, and syntactic control. Yet NAEP Reading results indicate that a large majority of U.S. eighth graders perform below the proficient level in reading. Limited daily reading reduces exposure to complex language and text structures, which in turn constrains students’ written expression.

7. Many students simply don’t enjoy writing—and that limits practice.

Across multiple surveys, relatively few students say that writing is something they enjoy or choose to do on their own. Research summarized by Penn State (PSU) on students’ views of writing highlights three recurring reasons students “hate” writing:

- They believe they don’t know how to write.

- They are unsure what teachers expect from an assignment.

- They feel disconnected from their own ideas by rigid, formulaic tasks.

When students dislike writing, they avoid it. Less practice means fewer chances to experiment with language, receive feedback, revise, and internalize effective writing strategies—keeping many stuck at the same level year after year.

What This Means for Schools and Classrooms

Taken together, these data points tell a consistent story: writing proficiency is a serious challenge from elementary school through college and into the workforce. The problem is not that students are incapable of writing; it’s that they often lack sustained instruction, frequent practice, and clear feedback in the kinds of writing that matter most for academic and professional success.

For classroom teachers and school leaders, this underscores the need to:

- Make writing a daily part of learning across content areas, not just in ELA.

- Pair writing tasks with rich reading, discussion, and modeling of mentor texts.

- Offer specific, actionable feedback focused on clarity, structure, and evidence.

- Design writing tasks that invite student voice and authentic purposes, not just compliance.

The trends are serious, but they are not fixed. With intentional, research-aligned writing instruction and more time on task, students can and do become stronger, more confident writers.