Differentiated Instruction: 10 Examples & Non-Examples

contributed by Christina Yu, knewton.com

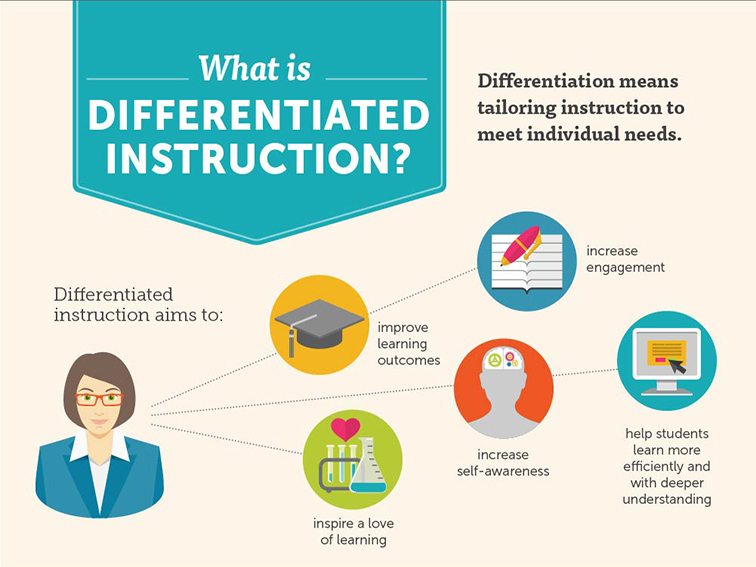

Differentiated instruction — the tailoring of content, process, product, and learning environment to address individual learner needs — has long been part of effective teaching practice. Teachers have always recognized that students vary in readiness, interest, background knowledge, and learning profiles. Through one-on-one coaching sessions, small group activities, individualized course packets, reading assignments, and projects, teachers address a range of student levels, interests, strengths, weaknesses, and goals in their classrooms.

Differentiated instruction is difficult and time-consuming work, and class sizes are increasing, which makes individualized learning harder to achieve. New adaptive learning technologies can support this work by recommending which concepts to focus on with a learner or an entire class and by providing instructors and students with information about concept-level strengths and weaknesses. These advancements help teachers make the most of class time so that students are neither overwhelmed nor bored.

For a deeper overview of differentiation in relation to personalized learning, see Differentiation vs. Personalized Learning .

5 Examples of Differentiated Instruction

These examples expand on common classroom practices and illustrate why they qualify as differentiation.

1. Varying sets of reading comprehension questions

Students working with the same text receive different sets of comprehension questions aligned to their readiness level or learning goal.

Example:

- One group focuses on literal recall and basic understanding using sentence frames or word banks.

- Another group analyzes character motivation or cause-and-effect relationships across chapters.

- A third group evaluates the author’s craft or point of view and how these shape the narrative.

In each case, the core learning target is consistent, but the questions adjust the process and product to better match student readiness.

2. Personalized course packets or individualized learning paths

A teacher assembles remediation or enrichment materials based on ongoing formative assessment data, not as a one-time modification.

Example:

- Some students receive mini-lessons on decoding or vocabulary, along with targeted practice passages.

- Others work with enrichment tasks that require extended writing, research, or analysis of multiple texts.

The materials are selected to address specific needs or to extend learning for students who are ready for more complexity.

3. Adaptive assessments that adjust in real time

An adaptive assessment becomes easier or harder depending on how a student is performing, allowing the teacher to identify strengths and gaps with greater precision.

Example:

- A student who answers several basic algebra items correctly is automatically moved to multi-step equation items.

- A student who struggles with multi-step problems receives scaffolded items that isolate key sub-skills.

The goal is not to label students, but to generate information that can guide subsequent instruction or intervention.

4. One-on-one coaching focused on individual learning needs

The teacher confers individually with a student to address a specific conceptual or skill-based challenge, using targeted feedback and modeling.

Example:

- A student who has difficulty making inferences in a text receives a brief, focused conference in which the teacher models a think-aloud, asks scaffolded questions, and then has the student practice with guided support.

The structure, content, and feedback are intentionally aligned with what that particular student needs to move forward.

5. Flexible small-group instruction based on strengths and needs

Students are placed into small groups that are formed around similar strengths, needs, or goals, and these groups are regularly adjusted based on new data.

Example:

- A fluency group practices phrasing and expression using short passages and immediate feedback.

- A comprehension group focuses on summarizing and identifying main ideas in increasingly complex texts.

- An extension group compares multiple texts and evaluates how different authors treat the same theme or concept.

Grouping is temporary and fluid, with students moving in and out of groups as their needs change. The purpose is to align instruction with specific learner profiles, not to track students permanently.

5 Non-Examples of Differentiated Instruction

These practices are sometimes mistaken for differentiation, but they do not meet the criteria because they change expectations rather than access to core learning goals.

1. Assigning advanced students to teach struggling peers

Peer tutoring can be a useful strategy, but it is not differentiated instruction by itself. Assigning stronger students to routinely teach peers shifts the responsibility for instruction away from the teacher and may not provide appropriate challenge for the so-called advanced students.

2. Giving advanced students no homework

Reducing the amount of work or removing homework for students who finish quickly is not differentiation. It lowers expectations and decreases opportunities for learning instead of adjusting the type or level of task to maintain appropriate challenge.

3. Grouping students into different classes based on ability

Long-term ability tracking or placing students into separate classes based solely on achievement is a structural decision, not differentiated instruction. Differentiation occurs within classrooms when teachers use ongoing assessment and flexible grouping to adjust content, process, and product.

4. Letting advanced students out of class early or giving them more free play time

Allowing students who finish early to leave class or engage in unstructured free time does not deepen their understanding. It reduces academic engagement and does not provide targeted extension work aligned with learning goals.

5. Simply allowing students to choose their own books from a list

Student choice is valuable, but choice alone is not differentiation. If students choose books from a list without guidance about text complexity, instructional focus, or reading purpose, the teacher has not intentionally adjusted instruction based on readiness, interest, or learning profile.

Frequently Asked Questions About Differentiated Instruction

What is the primary goal of differentiated instruction?

The primary goal of differentiated instruction is to ensure that all students can access core learning targets by modifying content, process, product, or learning environment based on readiness, interest, and learning profile, without lowering academic expectations.

Does differentiated instruction require a separate lesson plan for every student?

No. Differentiation does not mean designing an individual lesson plan for each learner. Instead, teachers use manageable structures — such as flexible grouping, tiered tasks, and choice within clear parameters — to respond to variation in a systematic way.

How is differentiated instruction different from personalized learning?

Differentiated instruction is typically teacher-designed and implemented within a shared classroom context. Personalized learning may involve more learner agency in setting goals, selecting tasks, or pacing work. For more detail, see Differentiation vs. Personalized Learning .

Is differentiated instruction supported by research?

Research supports practices that are central to differentiated instruction, including the use of formative assessment, scaffolded support, flexible grouping, and targeted feedback. Adaptive digital tools can further support these practices by providing timely information about student performance.

Does differentiation reduce rigor for some students?

No. Differentiation is not about lowering standards. Rigor remains constant while the path to achieving learning goals varies. Adjustments are made to how students engage with content, not to what they are ultimately expected to know and be able to do.