What Are The Most Common Grading Mistakes That Teachers Should Avoid?

Recently, I saw an old tweet that Justin Tarte shared about grading that’s indicative of a growing dissatisfaction with grading in education.

Don’t average scores. The new score should replace the old one. Mastery is mastery. It shouldn’t matter if it took 1 or 3 attempts to learn.

— Dr. Justin Tarte (@justintarte) September 19, 2014

Great point. Clearly this is an issue, even if it’s not new. So let’s take a look at what we’re doing, and how we’re doing it, shall we?

Should grades support, report, or punish?

If to support, support who?

If to report, report what, and to whom?

If to punish–to ‘hold students accountable like in the real world’ does it work like that? Does this work for the students?

Who Do Letter Grades ‘Work’ For?

Our current system of letter grades works well for many kinds of students. These are the students who learn to play the game. Form relationships with teachers. Can see the rules and parts of the games–which assignments matter, what the teacher values, how to format responses, how to use a rubric, how to study, and so on.

They also probably read and write fairly well. They value their own academic image–how people see them as a student. Their grades, GPA, and assortment of certificates and achievements are a source of intense pride for these students. The grades function as an extrinsic reward that pushes them to wade through whatever you put in front of them because they see themselves as ‘smart’ and successful, and that’s what smart and successful students do.

Letter grades may help students who ‘don’t like school,’ and come just for extracurricular activities. If they get the grades, they play; if not, they don’t. Grades simplify it all for them. In short, grades ‘work’ for students who come to school for any reason other than intellectual curiosity, literacy, or understanding.

Which means they don’t work for anyone.

What Should Grades ‘Do’?

We’ve talked in the past about alternatives to the letter grade, but this is something slightly different–looking at the mistakes we make in grading so that we can better design systems to communicate progress and performance to students, parents, and communities. And that’s what we want grades to do, right? Historically, grading has been expected to do two things:

1. First and foremost, give students some kind of idea how they’re doing, because–in our system of teaching and learning–we’re the content experts and how else would they know? (Hopefully it’s clear how crazy this is.)

2. Secondly, work as a living, breathing document of their academic travels–what they’ve studied and how they performed therein? (And hopefully here, it’s obvious how woefully grades perform in this role.)

What about “begin to communicate the nuance of the habits, character, knowledge, and critical thinking ability of the student right here in front of you”?

To not reflect failures, but affection? Potential? Creativity? There is a much larger conversation here about curriculum design, instructional design, literacy, learning models, and even technology. But if we isolate letter grades as they are used now in the system we have now with the thinking we use now, we are left with the following.

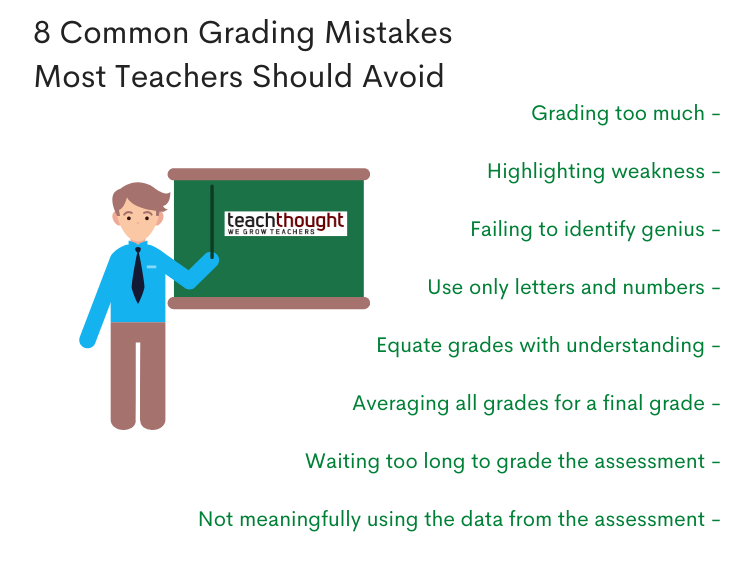

8 Common Grading Mistakes Most Teachers Should Avoid

1. Grading too much

Or worse, grading everything. What sort of masochism makes us think this is a good idea? It’s an incredible workload for you, and doesn’t do them any favors. An alternative? Be very selective about what you grade. Choose assignments that aren’t threatening, or confusing in exactly what it is that you’re measuring. In short, don’t grade ‘practice,’ grade landmark assignments.

Or have no landmark assignments at all–use a ‘climate’ of assessment that adjusts for the day-to-day drudgery of a classroom, and simply uses tests, quizzes, exams, projects, and the like as part-and-parcel to the process of learning.

2. Highlighting weaknesses

As used, grades highlight weakness, deficiency, and mistakes, which only motivates the most well-balanced, dedicated, and supported students. Offer corrections to performance rather than mechanisms to help students reflect.

Worse than emphasizing weaknesses, a common grading mistake many teachers make is to fail to uncover the genius and potential in every student. You might argue that ‘uncovering genius’ is not the job of a letter grade, but as the most visible artifact of almost every formal learning process, it’s hard to not see the effect of letter grades–and the powerful opportunity they represent.

3. Use letters and numbers

They’re reductive–artifacts from an old way of teaching and learning that valued the institutions and the flags they fly over the students themselves. There’s got to be a better way.

4. Equate grades with understanding

Most teachers worth their salt don’t make this mistake, but everyone else in education–from university admissions to parents to businesses to the students and their peers–do. Grades are, at best, a reflection of how well the teacher designed an assessment to reflect the language of a particular academic standard. At worst, they’re subjective conjurings that mislead.

5. Averaging numbers

See Justin Tarte’s tweet above. The learning process isn’t gas mileage.

6. Waiting too long to grade

After a certain point, it’s less about feedback or reporting, and more about students ‘wanting credit’ and teachers ‘needing to get grades in.’

7. Making them fixed

Rather than flexible. (See below.)

8. Not using the data in a meaningful way

That’s the point, yes–using data to revise planned instruction. Not using that data-and those corresponding grades–to make key adjustments that keep learning in their ‘ZPD’ is a problem, no?

Students:Letter Grades::You:Credit Rating

The closest analog I can think of for adults is the credit score. It acts as a record of what you’ve borrowed and what you repaid and have not repaid in an effort to predict–for someone that doesn’t know you well enough to make an evaluation of their own–the likelihood that you’ll repay. This predictor is reduced down to a number, arrived it by some combination of both accurate and mistaken reporting on behalf of the companies you’ve borrowed money from.

Within this number there is a lot going on–how frequently you borrow, how much you borrow, errors that claim you still owe money you paid, open accounts you forgot about years ago, and so on. And the next time you apply for credit somewhere–to buy a car, a house, even a cell phone–this is the number lenders go by, with cut scores of their own.

But even credit scores have multiple reporting agencies, mistakes drop off after a certain amount of time, and there are ways to get mistakes fixed, and strategies to reestablish credit after years of less-than-perfect decision-making.

As flawed a system as credit rating is–and it’s awful–it’s downright brilliant compared to letter grades. So how can we design that kid of flexibility in our grading system? Or better yet, something light years better? Parts of gamification in learning may help–especially badges, unlocks, and achievements–but that’s not it either.

As it exists, our current system for grading sets up the students that need it the most to fail. It provides a laundry list of weaknesses and failures that often haunt students the rest of their lives–paint them as this or not that. More often than not, they lock students out of possibility by offering inaccurate and subjective evaluations of performance without letting anyone in on the joke.

That’s the dirty little secret about grades–and the public doesn’t know. If we admit grades are exactly that–best guesses that summon an alphanumeric character to reflect a student’s performance in ‘our’ class, then they’re probably fine. But if we want something more–something student-centered that to “begins to communicate the nuance of the habits, character, knowledge, and critical thinking ability of the student right here in front of you“?

Well then, we’ve got some work to do. And the answer may lie in a combination of learning models and technology.