The Definition Of Critical Thinking

A reference introduction to the concept and its role in learning

Definition

Critical thinking is the suspension of judgment while identifying biases and underlying assumptions in order to draw accurate conclusions.

This definition emphasizes reflection, bias awareness, and evidence-based judgment.

The essay below explores how this idea functions in classrooms and in thought.

The Definition Of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is often mentioned in schools, policy language, and teacher preparation, yet rarely defined with any shared precision. It is used as praise, as shorthand for rigor, and sometimes as filler when meaning thins out. What follows is a clear definition, then a closer look at what critical thinking feels like and demands in practice.

Formal Definition

Critical thinking is the suspension of judgment while identifying biases and underlying assumptions in order to draw accurate conclusions.

This definition stresses restraint and awareness. It favors evidence over impulse and revision over speed.

A Simpler Way To Say It

Critical thinking is thinking to form judgment. Not reaction. Not confirmation of what you already believe. A pause. A turn inward to check what you think you know and why. It is an approach to thought rooted in patience and good faith. It tries to understand before deciding.

In schools the phrase appears often, though its meaning slides. Used loosely, it becomes decorative language. Its power fades when it is confused with activity, opinion making, or debate for its own sake.

When practiced honestly, critical thinking becomes the habit of using what you know while being prepared to change course when new information appears. It accepts that certainty can be premature. It treats questions not as hurdles but as the path.

For classroom approaches that support this work, see Teaching Critical Thinking.

Critical Thinking As Ongoing Thought

A paper from Harvard once noted that definitions of critical thinking “are quite disparate and are often narrowly field dependent.” It offered one: noticing assumptions, recognizing hidden values, evaluating evidence, and assessing conclusions. Philosopher Richard Paul and psychologist Linda Elder offered another: improving one’s thinking by taking charge of its structures and applying intellectual standards.

Both point toward the same work. A mind studies its own movement, adjusts when it finds error, and reaches toward clarity.

This kind of thinking does not end. It interacts with change. It grows alongside knowledge. It circles understanding rather than racing toward it. Tone matters here. So does intent.

Critical Pedagogy And Inquiry

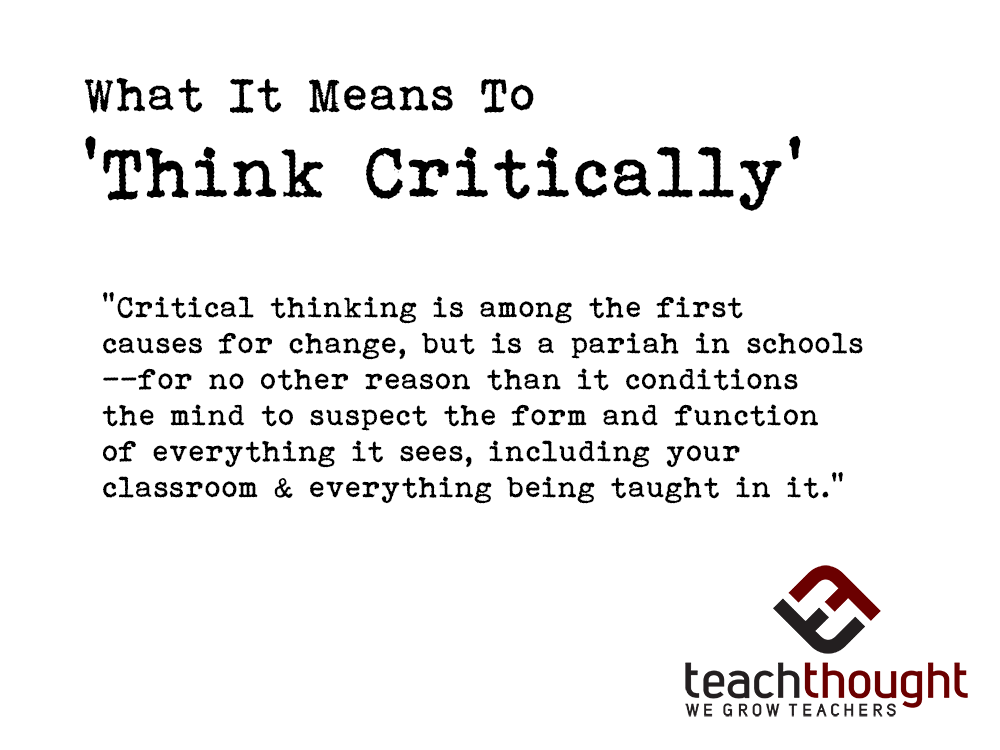

Schools invoke critical thinking, yet doing so often presses against systems that reward quick answers and closure. Sustained thought unsettles assumptions and questions structures. It does not always accept the lesson’s frame or the system’s goals.

Critical pedagogy overlaps here. It treats thought as analysis and as self-discovery. Science can seek neutrality and objectivity. Critical thinking accepts the self within the inquiry and moves anyway. It is not satisfied with one conclusion. It continues.

Classroom methods that make space for this include the practices collected in Critical Thinking Strategies.

Why The Term Feels Vague

For educators, critical thinking can feel like words such as democracy or global. We know they matter, yet we often use them without shared meaning. Ambiguity invites misuse. Over time, the term can lose its edge and become a gesture instead of a process.

Critical thinking, when real, can initiate change both personal and social. In many schools it is discouraged because it questions form and purpose. Still, thought without knowledge is idle, and knowledge without thought becomes mechanical. Each needs the other. They fold and reappear within one another.

Why It Matters

Critical thinking is not only an academic skill. It is a moral stance toward truth, doubt, revision, and patience. It belongs to the learner rather than the system. When students practice it, they begin to see themselves as thinkers who can choose what to believe and why. That shift creates agency.

For prompts that help students slow down and test a belief, explore Critical Thinking Questions.

Related Readings

Sources

- Facione, P. A. Critical Thinking: What It Is and Why It Counts.

- Paul, R., & Elder, L. The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking: Concepts & Tools.

- Ennis, R. H. “Critical thinking across the curriculum: A vision.” Topoi, 37(1).