6 Principles Of Genius Hour In The Classroom

by Terry Heick

Genius Hour in the classroom is an approach to learning built around student curiosity, self-directed learning, and passion-based work.

In traditional learning, teachers map out academic standards and plan units and lessons based around those standards. In Genius Hour, students are in control, choosing what they study, how they study it, and what they do, produce, or create as a result. As a learning model, it promotes inquiry, research, creativity, and self-directed learning.

Genius Hour has long been associated with Google, where employees are able to spend up to 20% of their time working on projects they’re personally interested in. The work is motivated intrinsically, not extrinsically. While many workplaces and schools now reference emerging tools—including AI—to support independent exploration, the underlying idea remains unchanged: curiosity fuels meaningful work.

The big idea is simple: people who pursue work driven by curiosity and purpose tend to be happier, more creative, and more productive. The same idea applies in classrooms today.

What’s The Difference Between Genius Hour And Traditional Learning?

Genius Hour provides students freedom to design their own learning during a dedicated portion of the school day. It allows learners to explore personal curiosity through a sense of purpose and ownership—while still working within the support and structure of the classroom.

A key distinction from fully self-directed learning is that Genius Hour is scheduled and bounded. Students receive meaningful autonomy, but within a timeframe, with guidance, feedback, and expectations for reflection and products of learning.

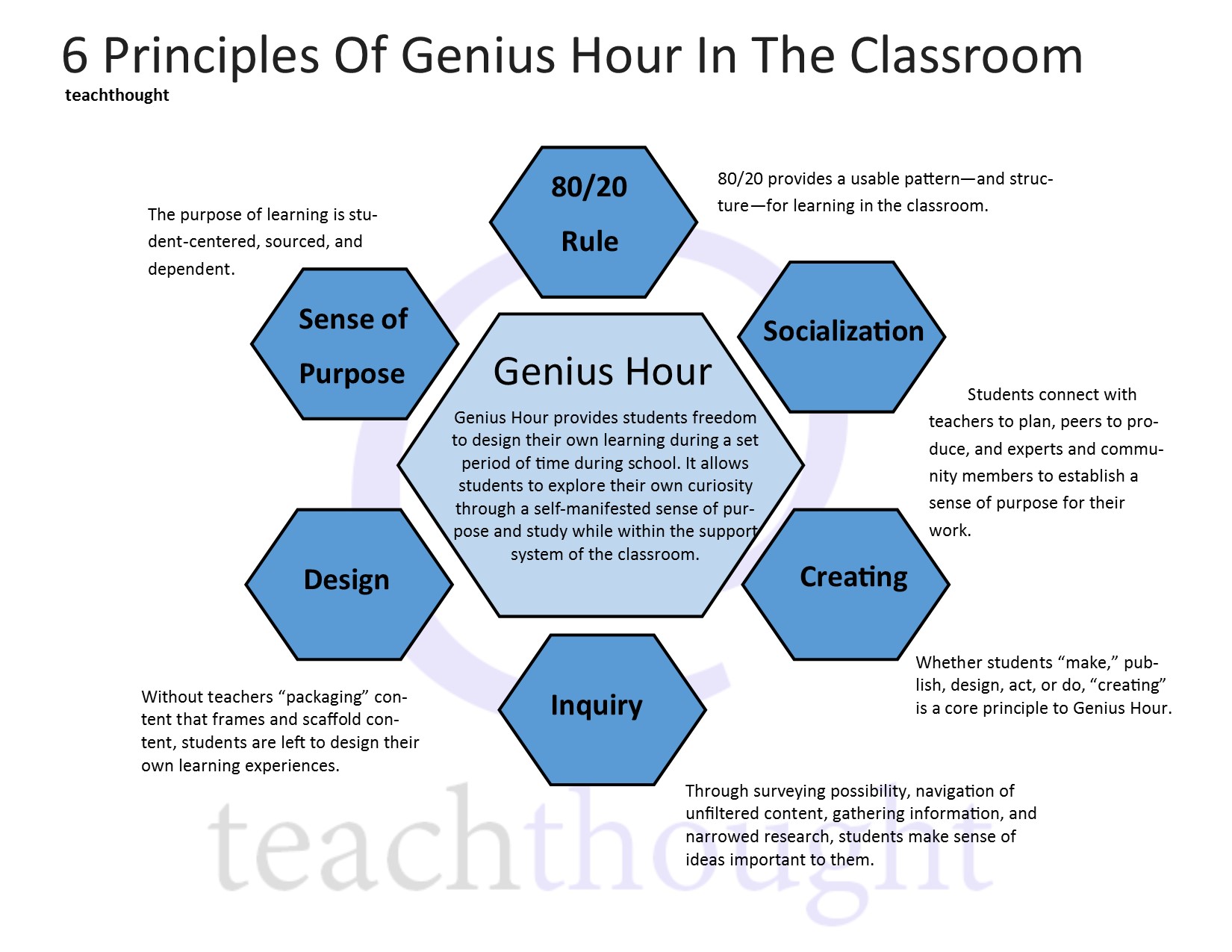

6 Principles Of Genius Hour

Sense of Purpose

Students identify meaningful questions, challenges, or creative pursuits. Motivation shifts from compliance to curiosity.

- A student passionate about animals researches endangered species and designs a “conservation awareness toolkit” for younger grades.

- A student fascinated by cooking creates a series of culturally influenced recipes and films short “how-to” videos.

- A student interested in video games studies character design and creates original character sketches and backstories.

Design

Students plan their process. Without pre-packaged learning, they must design their own experience and organize their work.

- Students draft a weekly timeline, including research time, interviews, drafting, and building or creating.

- Students outline needed materials (software, cardboard, yarn, paint, interviews, books, websites, etc.).

- Students write a project proposal and get teacher approval before starting.

Inquiry & Navigation

Students explore ideas, research openly, refine questions, gather information, and narrow toward a focused pursuit.

- A student who loves basketball starts broadly (“How does the NBA work?”) then narrows to “How do NBA scouts evaluate high-school athletes?”

- Students use classroom mini-lessons on evaluating sources to separate credible research from opinion or advertising.

- Students create a list of interview questions and email a coach, hobbyist, librarian, or parent expert for insight.

Create

There is always a visible product—something made, published, designed, built, performed, or shared.

- Students build a prototype toy using recycled materials and explain design choices.

- Students code a simple micro-game in Scratch to demonstrate cause-and-effect mechanics.

- Students publish a children’s picture book and read it aloud to primary-grade classrooms.

Socialization

Students collaborate with peers, conference with teachers, and seek feedback from experts or community members where helpful.

- Peer feedback circles where students ask for suggestions on research questions or presentation format.

- Short teacher conferences every week to set next goals and troubleshoot challenges.

- A student learning guitar records progress sessions and shares clips with a musician for feedback.

80/20 Rule

The structure gives a portion of time—an hour, a day per week, or similar—for student-driven inquiry. The rest of the schedule remains teacher-guided.

- Every Friday afternoon becomes Genius Hour; students show a weekly check-in product (notes, sketches, clips, research log).

- Students submit a simple weekly progress reflection: “What I tried → What worked → What I’ll do next.”

- Final products are shared in a showcase with posters, QR codes, demos, or quick presentations.

6 Principles Of Genius Hour In The Classroom