What Are Marzano’s 9 Instructional Strategies For Teaching And Learning?

Updated for practicing K–20 educators

In teaching, “research-based” is often used as shorthand for credibility. When teachers ask for strategies that work, what they usually want is something tested, transferable, and adaptable to real classrooms—from kindergarten writers to graduate-level seminars.

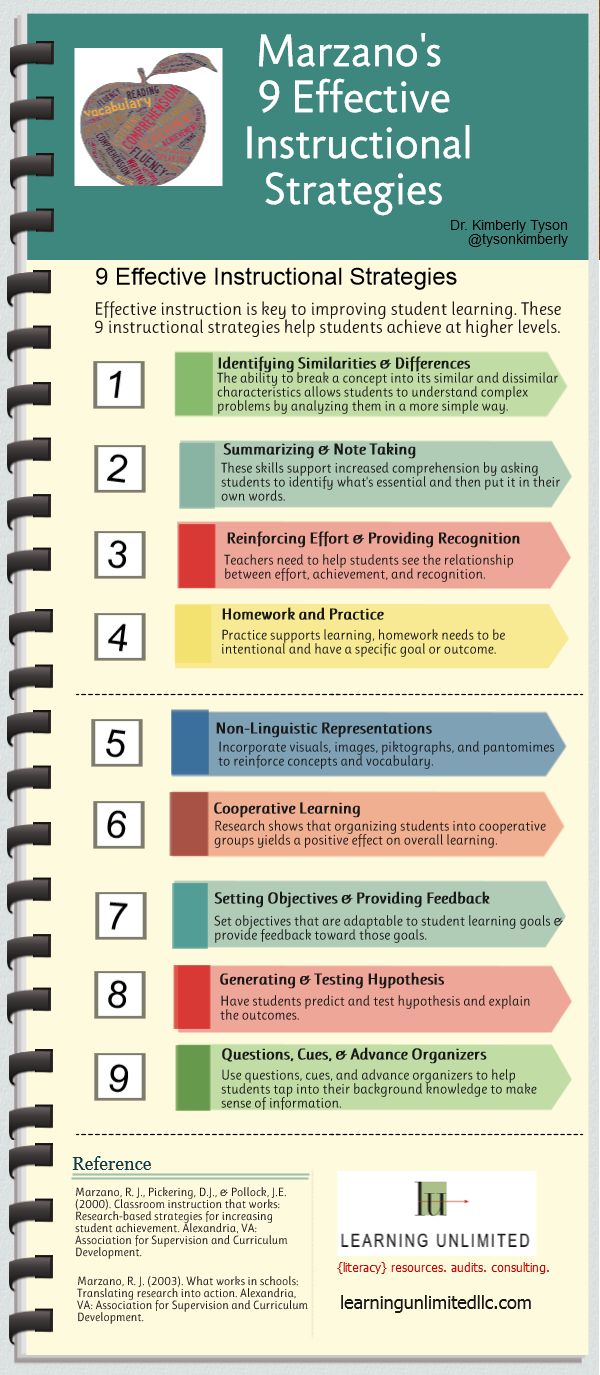

Robert Marzano’s work remains influential because it focuses on effect size: strategies that measurably improve student achievement across grade levels and content areas. In Classroom Instruction That Works, Marzano, Pickering, and Pollock synthesized decades of research into nine high-yield strategies that tend to support learning when they are used consistently and intentionally.

Below is a classroom-ready guide to Marzano’s nine instructional strategies, written for practicing K–20 educators and aligned with core themes of critical thinking, assessment, and teaching and pedagogy.

1. Identifying Similarities and Differences

Students deepen understanding by comparing, classifying, and creating analogies or metaphors. This strategy activates pattern recognition, which is central to how learners make sense of new content.

Classroom Examples

- Elementary: Students sort animals into categories using their own criteria (habitat, diet, number of legs) and then explain why they grouped them that way.

- Secondary: Students compare two historical revolutions, identifying structural similarities (causes, stages, outcomes) and contextual differences (time period, geography, political structures).

- Higher Ed: Students create analogies to explain complex theories (e.g., “Working memory is like a desk with limited space…”) and discuss where each analogy breaks down.

2. Summarizing and Note-Taking

Summarizing asks students to decide what is essential and what can be left out. Note-taking helps them track thinking in real time. Both support comprehension and long-term retention when students are taught how to do them, not just told to “take notes.”

Classroom Examples

- Elementary: After a read-aloud, students use sentence frames such as “The most important idea is…” and “First…, then…” to summarize the story.

- Secondary: Students use Cornell notes during a mini-lecture, then write a three-sentence summary that answers a guiding question posted at the start of class.

- Higher Ed: Students write a 100–150 word abstract of a peer-reviewed article, focusing on the research question, methods, key findings, and implications.

3. Reinforcing Effort and Providing Recognition

This strategy is not about generic praise. The goal is to help students see a clear link between effort, strategy use, and results. Recognition is most powerful when it is specific, credible, and focused on what students did, not who they “are.”

Classroom Examples

- Elementary: Students track their own reading practice minutes each week and write a short reflection on what changed because of that practice.

- Secondary: The teacher highlights a student’s revision work with comments such as, “You improved this thesis by narrowing the claim and adding a clear ‘because’ statement.”

- Higher Ed: Students submit a brief “effort and strategy log” with major assignments describing office hours, study groups, or additional sources they used and how those helped.

4. Homework and Practice

Homework and practice are most effective when they are focused, purposeful, and aligned with what students already understand. The research is stronger for short, targeted practice than for heavy, unfocused workloads.

Classroom Examples

- Elementary: Students complete a short set of math problems that all target a single skill introduced that day, with one stretch problem for advanced learners.

- Secondary: Students engage in low-stakes retrieval practice (short quizzes or flashcard routines) on key terms and concepts, with quick feedback at the start of the next class.

- Higher Ed: Weekly problem sets or micro-assignments (data analysis, terminology checks, case-study questions) that directly feed into larger papers or exams.

5. Non-Linguistic Representations

Non-linguistic representations ask students to represent knowledge visually, physically, or symbolically—not just through words. Diagrams, models, gestures, and mental images can all support understanding, especially for complex or abstract content.

Classroom Examples

- Elementary: Students draw story maps to show setting, characters, and events or create simple concept webs to connect vocabulary words.

- Secondary: In science, students model molecular structures with manipulatives; in social studies, they create timelines with icons and color-coding to represent events.

- Higher Ed: Students diagram a system—such as an ecosystem, a supply chain, or a neural pathway—and annotate it to show interactions, feedback loops, or constraints.

6. Cooperative Learning

Cooperative learning goes beyond “working in groups.” The research is strongest when groups are small, roles are clear, tasks require interaction, and accountability is both individual and collective.

Classroom Examples

- Elementary: In math, students solve a problem in groups of three with defined roles (Facilitator, Recorder, Checker), then rotate roles for the next task.

- Secondary: In a jigsaw structure, each student reads a different article on a shared topic, becomes an “expert,” and then teaches the key ideas to their group.

- Higher Ed: Inquiry teams divide a research question into sub-questions, assign responsibilities, and synthesize findings into a shared presentation or policy brief.

7. Setting Objectives and Providing Feedback

Learning goals give students a target. Feedback helps them see where they are relative to that target and what to do next. Clear objectives and timely feedback support self-regulation and more efficient use of practice time.

Classroom Examples

- Elementary: The teacher posts “Today we will…” statements in student-friendly language and briefly reviews how the activity connects to the goal.

- Secondary: Students receive rubric-based comments that focus on one or two criteria at a time (e.g., clarity of claim, quality of evidence) instead of broad, general remarks.

- Higher Ed: In writing-intensive courses, professors provide annotated exemplars and feedback that explicitly links comments to assignment criteria or program outcomes.

8. Generating and Testing Hypotheses

Although it is often associated with science, this strategy is useful in any subject where students can make predictions, test ideas, and revise their thinking based on evidence. It shifts the focus from “learning the answer” to “figuring out why.”

Classroom Examples

- Elementary: Students predict which materials will best insulate ice and design a simple test to see which container keeps the ice frozen longest.

- Secondary: In English, students propose a hypothesis about a recurring symbol in a novel (“This symbol represents…”) and then gather textual evidence to test and refine their interpretation.

- Higher Ed: Students use datasets or simulations to test hypotheses about economic trends, ecological systems, or social behaviors and then interpret limitations of their findings. In many classrooms, this kind of work naturally overlaps with project-based learning.

9. Cues, Questions, and Advance Organizers

Cues, questions, and advance organizers help students connect new material to what they already know. Strong questions and well-designed organizers prepare learners to notice patterns, anticipate key ideas, and integrate new information more efficiently.

Classroom Examples

- Elementary: Before a science unit, the teacher uses a simple picture-based organizer and asks, “What do you notice?” and “What do you already know about this topic?”

- Secondary: Students complete a Know–Wonder–Learn (KWL) chart before reading a complex article and return to it afterward to update their understanding.

- Higher Ed: At the start of a new module, the instructor provides a conceptual framework or outline of key ideas so students can see how individual lectures fit together. This work pairs well with resources on questioning and inquiry in the classroom.

Putting the 9 Strategies Together

These nine strategies are not a checklist to run through every day. They are flexible tools that can be combined and adapted based on content, students, and context. They also connect naturally to other frameworks teachers already know, including Bloom’s Taxonomy verbs, project-based learning, and broader work on research-based pedagogy.

Used thoughtfully, Marzano’s strategies can help you:

- Clarify learning goals and how students will reach them

- Design tasks that move beyond coverage toward deeper understanding

- Support students’ metacognition, reflection, and ownership of their own learning

The most important move is not simply naming the strategy, but aligning it with a clear purpose in your lesson or unit and making that purpose visible to students.

References

- Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D. J., & Pollock, J. E. (2001). Classroom Instruction That Works: Research-Based Strategies for Increasing Student Achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

- Beesley, A. D., Apthorp, H., & colleagues. (2010). Classroom Instruction That Works: Research Report. Denver, CO: McREL International.

Marzano’s 9 Instructional Strategies In Infographic Form