A Brief History Of Neuroscience Of Learning

contributed by Stewart Hase and Chris Kenyon

The science of learning, discovering how people learn, as opposed to the philosophy of learning and education that goes back to Egyptian times, can be sheeted back to around the tenth century.

However, it is only recently that advances in neuroscience and the capacity to investigate the functioning of the brain have really enabled us to see what happens when we learn. In the past ten years, our understanding has risen exponentially.

Commonly used definitions of learning have failed to keep pace with these advances in neuroscience and appear to be rather outmoded (Hase, 2010). Learning is often referred to as knowledge being gained through study, instruction or scholarship or the act of gaining knowledge. Many accepted psychological definitions refer to learning as being the result of any change in behaviour that results from experience. Discussions about learning mostly concern the education process rather than what happens in the brain of the learner – where learning really takes place.

It’s important to establish at this point that we are not attempting a neurological reductionist explanation of learning. Clearly learning is a complex interaction of myriad influences including genes, neurophysiology, physical state, social experience and psychological factors.

However, we suggest that understanding what is happening in the brain when we learn might provide important new insights into what is happening to the learner in the education or training experience. When we learn something, networks of neurons are established that can later be accessed, what we call memory (e.g. Benfenati, 2007). Laying down larger and larger numbers of pathways creates an increasingly complex matrix (Willis, 2006). Thus, old and new pathways influence each other in potentially quite dramatic ways through a process of activation and association (Khaneman, 2011). It appears that humans seek to make patterns from their experience.

Furthermore, it is hard to predict just what the effect of this pattern-making from the mix of new and old learning might be. We might be aiming for a simple change in behaviour, a new competency perhaps. But the learner may end up making a whole bunch of cognitive leaps and end up seeing the world in completely different ways: ways not necessarily defined by the curriculum, which now becomes a constraint. Thus, every brain is different. Our experiences mean that each person will selectively focus on different issues, concerns, and applications of the things they are learning. They will be asking different questions in their minds, testing their own hypotheses, making their own conclusions as a result.

John Medina in ‘Brain Rules’ (2008a) gives a great example of the neuroscience underpinning the above assertion. The part of the cerebral cortex for the use of the fingers of the left hand in a right-handed violinist is extremely dense with cells. Presumably, this is the result of practice. People who do not play the violin do not have this density in the same place but presumably have denser areas elsewhere depending on what their areas of interest might be.

So, the response of the individual to new information, to new experiences will vary a great deal due to this unconscious selection. In fact, it may take years before a person has that ‘ah, ah’, moment. This all questions the fixed curriculum, didactic teaching, teacher-directed learning, and many of the methods we currently use. The notion of brain plasticity recently popularized by Doidge (2007) also provides some fascinating insights into how people learn.

More importantly, these insights have led to the development of highly focused techniques being used to target very specific areas of the brain. Neuroscience (and resources for brain-based teaching) research shows that the more we actually ‘do’ with a new piece of learning the greater the number of neuronal pathways that are established and cemented in place through the development of matrices of dendrites mediated by the release of neurotrophins (Willis, 2006). This supports previous well-known evidence that an enriched environment leads to increased development of the brain (Rosenzweig et al., 1962), and this finding is used in a number of educational contexts.

Exploration is far more effective for learning than using rote methods or passive processes. It is also interesting that the more satisfying, engaging, and perhaps exciting the education process, the more internally reinforcing it is to the learner through the release of dopamine (Willis, 2006). There are parts of the brain that are responsible for watching others, forming hypotheses, testing assumptions, and generally exploring (Gopnik et al., 2000). These skills and the relevant brain activity is seen in children – they are great learners. Repetition using different senses, application, and providing context or at least finding out what the learner’s context might be are critical to learning. In fact the more elaborately we experience something, the more likely we are to learn it (Craik and Tulving, 1975; Gabrielli et al., 1996; Grant et al., 1998; Hasher and Zacks, 1984; LeDoux, 2002; Medina, 2008b).

The converse is also true. The human attention span has been shown to be limited to about ten minutes when stimulation is low and there is an absence of activity (Johnstone and Percival, 1976; Middendorf and Kalish, 1996). Humans are built to be active, to do things, to apply, to explore, and to be curious. They are not designed to sit still and pay attention to the same stimuli for long periods – this induces a state of trance, as most hypnotists know. Our understanding of learning can best be summarized by Sumara and Davis (1997, p. 107) as: ‘. . . a process of organizing and reorganizing one’s own subjective world of experience, involving the simultaneous revision, reorganization and reinterpretation of past, present and projected actions and conceptions’. Learning results in a whole new set of questions to ask, based on their new understanding, not only different from their colleagues but also outside the curriculum, if not well beyond it.

These new questions provide a motivation to learn. Perhaps the example below will illustrate what is meant by this. Until 1697 all known swans were white. Nobody had seen a black swan, so in English poetry the idea of a black swan represented the impossible. In that fateful year Willem de Vlamingh, a Dutch explorer, discovered black swans in what was later to become Western Australia. Suddenly, the whole idea of swans changed, as did the metaphor for impossibility. The change eventually led Nassim Taleb in 2004 to write about black swan events.

These are unpredictable things that happen, good and bad, that have profound effects on the world. They are things we often fail to plan for and, in fact, we cannot prepare for, except by building resilience in people and in organizations. Taleb’s novel conceptualization of the black swan leads to a complete rethinking of what we mean by strategic planning by focusing on building capacity for dealing with uncertainty.

Heutagogy also draws on the notion of capability (e.g. Stephenson, 1996; Stephenson and Weil, 1992) by distinguishing between the acquisition of knowledge and skills or competencies and the deeper cognitive processes described above. Capability involves using competencies in new contexts and challenging situations. It is about the unknown and the future, rather than the routine. In demonstrating capability the person is making a host of new neuronal connections, creating new hypotheses, and testing them mentally and physically, in understanding the best way to proceed.

At the same time, capability requires the learner to have a high degree of self-efficacy in their ability to learn and access appropriate resources. Capable people also recognize the need to work with others to deal with new and changing circumstances.

Ed note: This post has been republished from a series on self-determined learning from Stewart Hase and Chris Kenyon. Stewart’s site, Heutagogy Community of Practice, is a useful resource for reading on Self-Determined Learning. The first post was Shifting From Pedagogy to Heutagogy In Education.

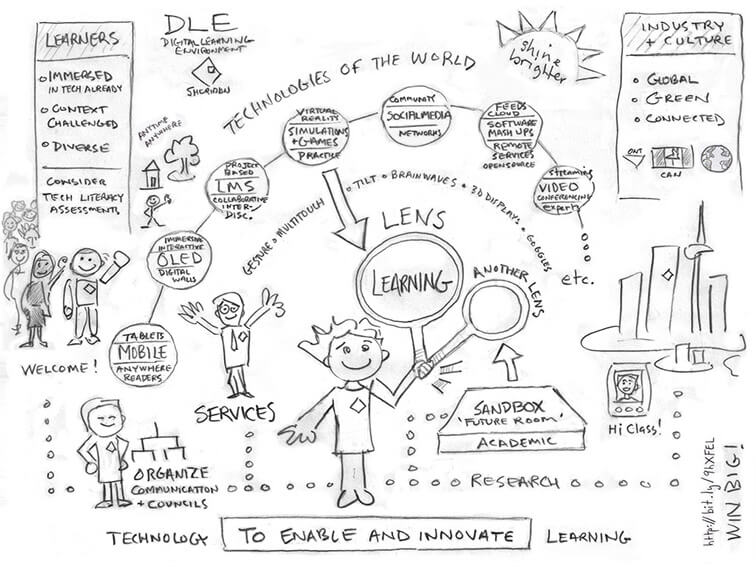

Learning Beyond The Curriculum; adapted image attribution flickr user danzen