Misunderstanding The Gradual Release Of Responsibility Framework

Assess the extent to which students, unprompted, use the strategies when reading new text before ‘releasing responsibility.’

How People Misunderstand The Gradual Release Of Responsibility Framework

by Grant Wiggins, Authentic Education

Yes, reading strategies–and explicit teaching of them–make a considerable difference, as my previous four blog posts here, here, here, and here make clear. And there is much to like about the idea of the gradual release of (teacher) responsibility in the teaching of those strategies for reading – or anything else where we want skillfulness. The approach is interactive, empowering for kids, easy for most teachers to grasp and implement, and grounded in research.

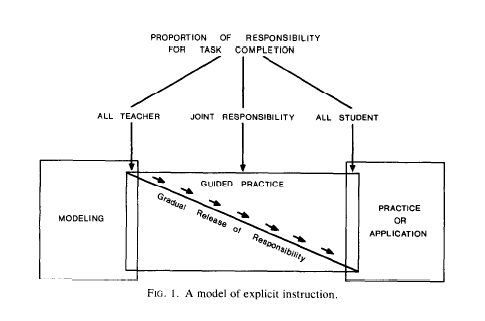

Here is the original graphic of the Gradual Release of Responsibility idea from the 1983 paper by Pearson & Gallagher:

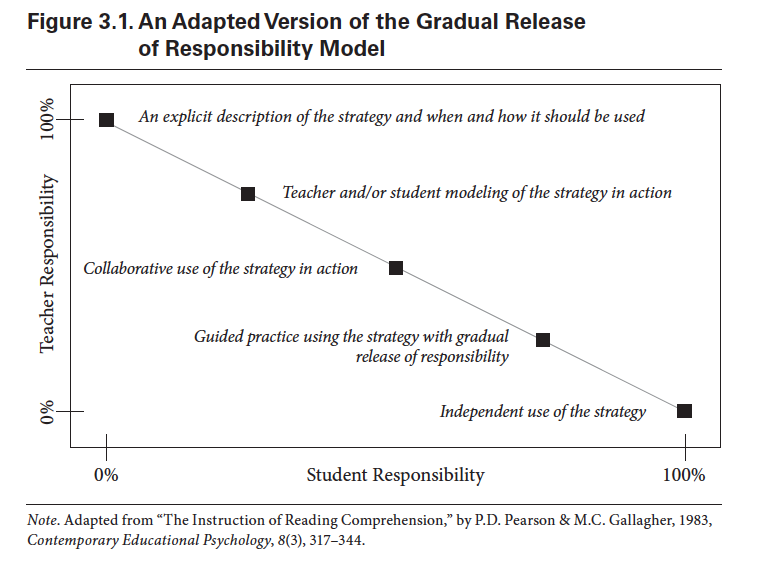

Here is a more recent graphic version from Duke & Pearson (2002):

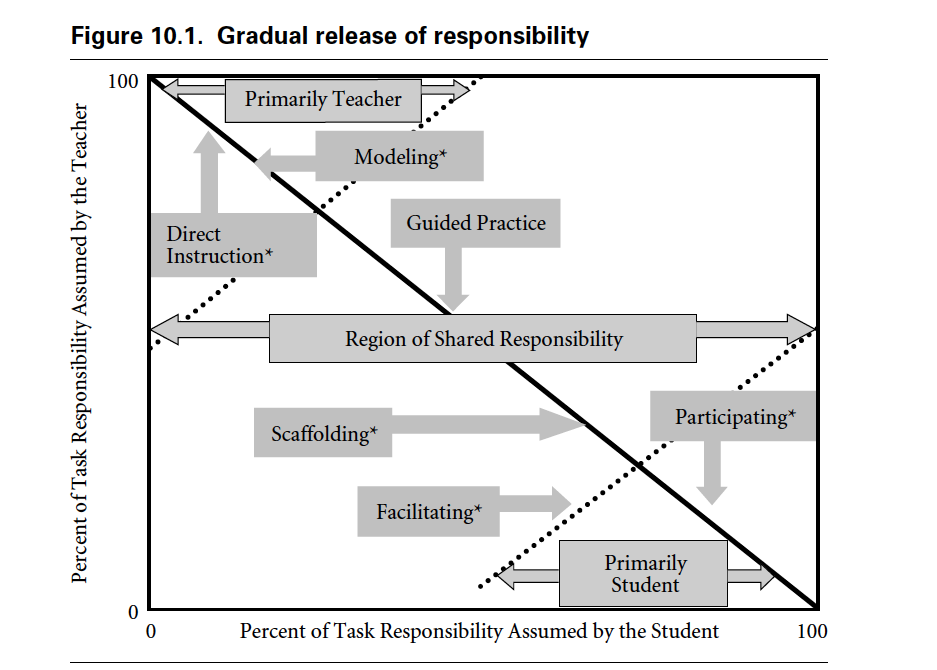

Here is a more recent version still, in the 2011 article on comprehension strategies by Duke, Pearson, Strachan & Billman, their chapter in a newer edition of What Research Has to Say About Reading Instruction (IRA, 2011):

Here is the text description accompanying the most recent graphic:

The model we recommend for teaching any comprehension strategy is the gradual release of responsibility (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983). In this model (see Figure 3.1), responsibility for the use of a strategy gradually transfers from the teacher to the student through five stages (Duke & Pearson, 2002, pp. 208–210):

- An explicit description of the strategy and when and how it should be used. “Predicting is making guesses about what will come next in the text you are reading. You should make predictions a lot when you read. For now, you should stop every two pages that you read and make some predictions.”

- Teacher and/or student modeling of the strategy in action. “I am going to make predictions while I read this book. I will start with just the cover here. Hmm…I see a picture of an owl. It looks like he—I think it is a he—is wearing pajamas, and he is carrying a candle. I predict that this is going to be a make-believe story because owls do not really wear pajamas and carry candles. I predict it is going to be about this owl, and it is going to take place at nighttime….”

- Collaborative use of the strategy in action. “I have made some good predictions so far in the book. From this part on I want you to make predictions with me. Each of us should stop and think about what might happen next…. Okay, now let’s hear what you think and why….”

- Guided practice using the strategy with gradual release of responsibility. Early on… “I have called the three of you together to work on making predictions while you read this and other books. After every few pages I will ask each of you to stop and make a prediction. We will talk about your predictions and then read on to see if they come true.” Later on… “Each of you has a chart that lists different pages in your book. When you finish reading a page on the list, stop and make a prediction. Write the prediction in the column that says ‘Prediction.’ When you get to the next page on the list, check off whether your prediction ‘Happened,’ ‘Will not happen,’ or ‘Still might happen.’ Then make another prediction and write it down.”…

- Independent use of the strategy. “It is time for silent reading. As you read today, remember what we have been working on—making predictions while we read. Be sure to make predictions every two or three pages. Ask yourself why you made the prediction you did—what made you think that. Check as you read to see whether your prediction came true. Jamal is passing out Predictions! bookmarks to remind you.”

Great–a proven guide to teaching each strategy! What’s not to like?

The Real Last Step

Well, a key step towards the goal of the strategies is missing. In light of our discussion so far, do you see the critical mistake that users of this approach might easily make by relying only on these graphics and the explanatory text?

Look at the so-called last step: independent practice. That is surely not the last step in developing self-regulated meaning-making. The last step is the arguably fluent, flexible, and self-regulated selection and use from a repertoire of strategies – namely, successful transfer of learning for comprehension.

The authors understood the issue, as made clear in another section of their chapter:

Effective teachers of reading comprehension help their students develop into strategic, active readers, in part, by teaching them why, how, and when to apply certain strategies shown to be used by effective readers (e.g., Duke & Pearson, 2002). Although many teachers teach comprehension strategies one at a time, spending several weeks focused on each strategy … this may not be the best way to organize strategy instruction (Reutzel, Smith, & Fawson, 2005)…. Studies and reviews of various integrated approaches to strategy instruction, such as reciprocal teaching (e.g., Palincsar & Brown, 1984), have suggested that teaching students comprehension routines that include developing facility with a repertoire of strategies from which to draw during independent reading tasks can lead to increased understanding (e.g., Brown, 2008; Guthrie, Wigfield, Barbosa, et al., 2004; Spörer, Brunstein, & Kieschke, 2009).

Alas, no practical guidance is offered here on how to accomplish such an integrated approach.

(Oddly, the authors dropped a paragraph from their earlier 2002 version of this article that offers some guidance:

“Ongoing assessment. Finally, as with any good instruction, comprehension instruction should be accompanied by ongoing assessment. Teachers should monitor students’ use of comprehension strategies and their success at understanding what they read. Results of this monitoring should, in turn, inform the teacher’s instruction. When a particular strategy continues to be used ineffectively, or not at all, the teacher should respond with additional instruction or a modified instructional approach. At the same time, students should be monitoring their own use of comprehension strategies, aware of their strengths as well as their weaknesses as developing comprehenders.)”

The Unintended Consequence

Because of the well-known graphic, it becomes ironically far too easy for a teacher to incorrectly think that gradual release on each strategy, in the way laid out in the graphics, should somehow culminate in a self-regulated repertoire that transfers. Alas, that cannot cause transfer – as common sense and the research reveal. Recall Pressley’s blunt comment from an earlier post:

“Rather than teaching students how to become self-regulated learners, teachers seem to expect behaviors would naturally develop through prompted questions. There is of course no evidence that such prompting leads to anything like active self-regulated use of comprehension strategies.”

Yet, despite these warnings in the literature, I have seen this problem first-hand time after time in classrooms: teachers follow this graphic in organizing the teaching of all the strategies–and, worse, rarely assessing the extent to which students, unprompted, use the strategies when reading new text.

Tomorrow, we’ll look at transfer, and how we can think of it differently for more effective teaching.

This post is excerpted from a post that first appeared on Grant’s personal blog; Misunderstanding The Gradual Release Of Responsibility Framework