How Learning In Your Classroom Is Different Than Learning In The Real-World

by Terry Heick

Quick post with a basic premise: how are ‘school learning’ and ‘real world learning’ different?

For now, we’re going to skip the more crucial discussions about whether or not this is bad, how to minimize it, why this is the case, and so on. Many of these have been had in books and TED talks and on social media. For now, just a quick itemization of some of the more common ways classroom and ‘real world’ learning are different.

Some of this is due to the nature of outcomes-based learning. In 50 Ways To Measure Understanding, in discussing the idea of ‘measuring’ understanding I said:

Itemizing ways to measure understanding is functionally different than students choosing a way to demonstrate what they know—mainly because in a backward-design approach where the learning target is identified first, that learning target dictates everything else downstream.

If, for example, a student was given a topic and an audience and was allowed to ‘do’ something and then asked to create something that demonstrated what they learned, the result would be wildly different across students. Put another way, students would learn different things in different ways.

By dictating exactly what every student will ‘understand’ ahead of time, certain assessment forms become ideal. It also becomes much more likely that students will fail. If students can learn anything, then they only fail if they fail to learn anything at all or fail to demonstrate learning anything at all. By deciding exactly what a student will learn and exactly how they will show you they learned it, three outcomes, among others, are possible:

1. The student learned a lot but not what you wanted them to learn

2. The student learned exactly what you wanted them to learn but failed to demonstrate it in the assessment

3. The student failed to learn

Note, not all of these are always true. There are exceptions–sometimes mesmerizing ones with elegant solutions to modern challenges of formal, K-12 education. The idea here is to simply become more aware of the kinds of shifts students must make when transferring learning and skills and understandings from the classroom to their lives.

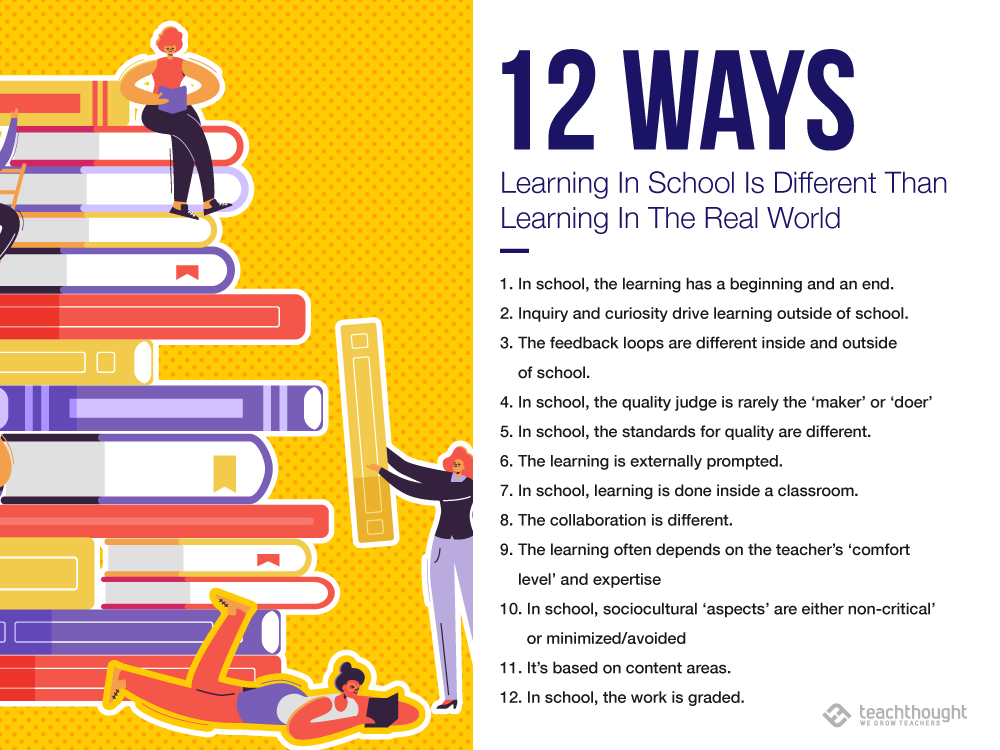

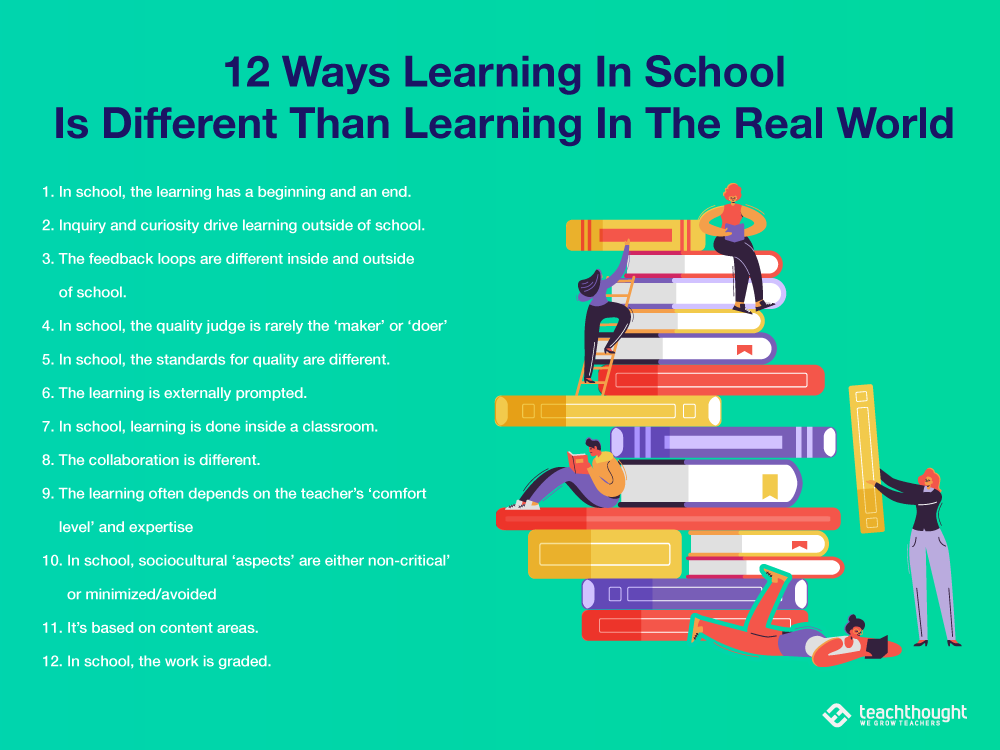

12 Ways Learning In School Is Different Than Learning In The Real World

1. In school, the learning has a beginning and an end.

Because school days begin and end and lessons and units and school years do too, any learning done in school has to as well. The learning in school is done in short bursts based on school schedules, lesson and unit design, etc.

2. Inquiry and curiosity drive learning outside of school.

School learning can benefit from curiosity and inquiry but in almost every case, can happen–to be lifelessly graded–without it. In the real world, curiosity, inquiry, and tight feedback loops drive learning.

3. The feedback loops are different inside and outside of school.

That is, the timing, immediacy, duration, and source–and thus effect–of the feedback loops are different in a classroom than they are in the real world.

4. In school, the quality judge is rarely the ‘maker’ or ‘doer’

Or their peers or an authentic audience or ‘client’ but rather the external and singular (e.g., the teacher, a computer algorithm, etc.) This ‘quality judge’ is usually a person (i.e., teacher) and singular and often not an ‘expert’ or able to give the time and care and affection a topic or skill or project deserves due to extraordinary time demands made on them elsewhere

5. In school, the standards for quality are different.

In school, the source for the standards for quality of work is often external and almost always ‘singular’ (come from one person). Among other effects, this dictates the depth, quantity, timing, and ‘framing’ of the learning feedback.

6. The learning is externally prompted.

And done so by the above ‘quality judge.’ This means it is rarely based on curiosity, genius, or intended application.

7. In school, learning is done inside a classroom.

Unless it’s in one of the types of blended learning or project-based learning somehow done/placed in the ‘real world,’ school learning is done in school.

Even if it’s not, the ‘walled garden’ of learning is institutionally-centered and standards-driven rather than based on curiosity, buying/selling, creativity, or some other ‘more authentic’ context.

8. The collaboration is different.

In school, the people, timing, purpose, and nature of any collaboration are different than the real world. Among other results, this means that collaboration that does result is rarely authentic or ‘student-centered.’

9. The learning often depends on the teacher’s ‘comfort level’ and expertise

This one isn’t the teacher’s fault–it’s just inherent to an outcomes-based, teacher-led classroom. It’s not only difficult for a teacher to teach something they don’t know or aren’t comfortable with, but it can also reduce student learning or even be dangerous (e.g., privacy concerns in social media, for example).

10. In school, sociocultural ‘aspects’ are either non-critical’ or minimized/avoided

In the classroom, culture is often ‘added in.’ In the real world, culture is (generally) often the foundation or focus of the learning and learning process. Gender, race, poverty, sexuality, politics, dance, art, and so on are rarely the driving force behind learning while in the real world, obviously, they are.

11. It’s based on content areas.

While learning in the real world can sometimes be based on ‘math’ and ‘language arts,’ more commonly those content areas are simply sources to inform and improve the learning process itself. For example, if someone wants to learn to build a fence, they might learn to calculate area and perimeter to accomplish that goal.

In school, those content areas are ‘mastered’ in hopes that one day students might need to use that skill or apply that knowledge.

12. In school, the work is graded.

And those grades–rather than the work and process and products and networks created while doing that graded work–tends to ‘stick’ with students.