What Does The Black Lives Movement Look Like In Your Classroom?

by Terry Heick

In lieu of the unprecedented (in my lifetime) civil rights events of the last two months, I’ve resisted writing about it all–the Black Lives Movement, specifically–so far because rather than merely creating a digital gesture for the sake of public alignment and ‘PR,’ I wanted to have a more clear sense of what was actually happening.

While I’m not sure I do understand this very nuanced and crucially important circumstance well enough to say anything worth knowing, today–Juneteenth, the formal recognition of the end of slavery in the United States–seems to be as good a day as any to at least try.

On Movements In General

It’s unsettling and disappointing but perhaps not surprising to see the number of companies, social media influencers, brands, and organizations spending millions of dollars on campaigns meant to align themselves with ‘the movement’ (i.e., the Black Lives Movement) rather than to bring their resources and talents to bear on the cause for the need of the movement to begin with.

Insufficient behaviors (e.g., ‘gestures) and appearances and generalizations are a part of what got us in this position. Apparently, previous movements involving the environment, war, organic food, alternative fuels, and more have not helped us see the failures and limitations of ‘movements.’ Eventually, movements stop once our energy wanes or another ‘movement’ demands our attention.

In regards to the Black Lives Matter movement specifically, if we are going to see it all as a ‘thing’ or system of things, we have to also see its scale and context and history–and then describe it all with language that honors that scale and context and history with unflinching accuracy.

That is, we have to see ‘it’ in its entirety: causes and effects, characteristics and nuance, truths and red herrings, explicitness and implicitness, art and science, grace and violence, past and future.

My fear is that we are unwilling to do the careful and clear thinking necessary to do so.

My hope is that other means (beyond careful and clear thinking) can produce similar results.

On Our Unwillingness To Tell Our Story Of America As It Is

Why is the Black Lives Matter movement necessary? Because as a nation, we don’t share the same reverence for black lives as we do for white. The sanctity of the lives of African Americans has never been fully realized in America. To say that it wasn’t restored after slavery would imply that it was there before slavery.

While Christopher Columbus often symbolizes our collective failure to teach American history clearly, his relative vileness is a small wound compared to the legacies of slavery and institutional racism in the United States.

For example: That it’s even remotely possible that lynchings continue to occur in 2020 is a useful setting for our thinking.

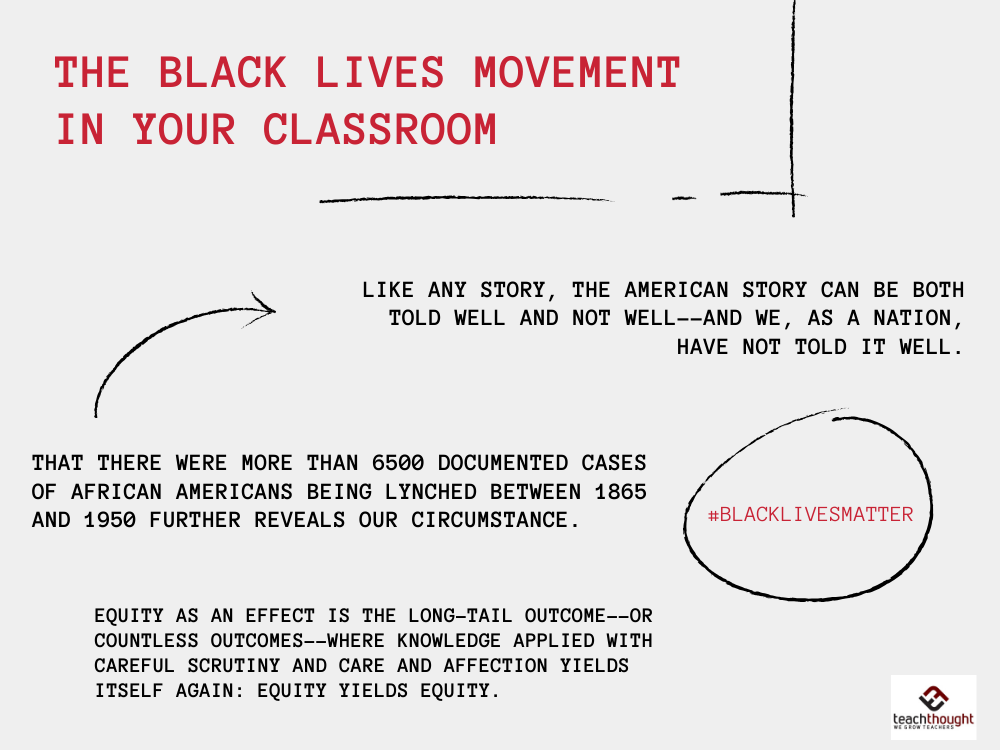

That there were more than 6500 documented cases of African Americans being lynched between 1865 and 1950 further reveals our circumstances and clarifies that ‘this’ isn’t merely a ‘stain’ or ‘shameful historical footnote,’ but clear and compelling data that racism and violence are as much a part of our history as freedom and democracy.

Slavery, lynchings, segregation, Jim Crow–these are all part of our collective ‘story’ and every bit as American as baseball and free markets and shopping malls and the automobile.

Like any story, the American story can be both told well and not well–and we, as a nation, have not told it well. Juneteenth and Emmett Till and Black Wall Street and George Wallace and countless other stories make many Americans the wrong kind of uncomfortable.

In the selectiveness of our stories, we fail to keep our story intact.

That is, we fail to communicate with any completeness or honesty where our nation has come from and thus, where it might be going.

On The Incomplete Story Of America

I. Historically, the story of America has been, in part, our unwillingness to tell our story.

II. We instead have a preference to tell many (carefully selected) stories as vignettes.

III. This is in contrast to telling our complete story.

IV. The story of America remains, then, untold and thus unknown.

V. This is further complicated by the fact that the story of America continues even as we tell–or fail to tell–it.

VI. At any time, we can tell our story–though never free from bias and interpretation because these are inherent in the human condition.

VII. The effort to tell a more complete story can then become part of our story. This can be seen as a kind of cycle of self-realization.

On The Threat Of What’s Specific Becoming General Again

In response to the Black Lives Matter movement, many have responded that ‘all lives matter.’ Of course, all lives do matter. However, the sanctity of white lives isn’t in question in the United States.

This is especially true for white, heterosexual lives and becomes even more true for rich, white, powerful, English-speaking heterosexual men. And so on. There are levels to everything and in America, being transexual or black or poor or Hispanic or homeless or jobless isn’t just less safe than affluent and white and employed and English-speaking, it’s downright dangerous (something Public Enemy, Brand Nubian, Jeru the Damaja, Ice Cube, 2pac, NWA, Ice T, Arrested Development, and scores of others have been saying for decades in hip-hop).

And while the ‘All Lives Matter’ response egregiously misses the point, a related threat is shifting the focus from African American safety and opportunity and well-being to a more general ‘return to basic human dignity’ or ‘respect’ or ‘kindness.’ To hear someone wonder why we ‘have to’ focus on Black lives and race only underscores their privilege. To hear them ‘disagree’ that racism is an issue—especially when they believe that opinion is supported by data—only further demonstrates the scale of race and racism in the United States. It’s so pervasive that it’s nearly invisible.

Zooming away from the centuries-old tragedy of ‘race relations’ in the United States to focus on more general categories of ’empathy’ or ‘equality’ is a refusal to honor the complexity and urgency of the issue. It’s trading the comfort of the majority for justice of the minority at the cost of everyone.

Moving from ‘Black Lives Matter’ to ‘Treat others the way you want to be treated’ is as useful as standing outside of a house fire giving a speech about leaving candles unattended. To confront the issues of race in the United States, we have to first not look away. Then, suitably informed, we have to describe what we see as clearly as we can without resorting to age-old verbal reflexes about the things you personally believe are and are not true about race.

As with any cultural ‘thing’ that endures, a challenge here is trying to see what’s actually going on from multiple perspectives–historically, culturally, socially, politically, technologically, etc.–without losing the thing itself.

On Equity In Education

And now I realize that I haven’t even really gotten to the idea of equity in education, specifically. So here are a few thoughts:

I. Ideally, the pursuit of equity is both a cause and an effect–the natural product of a child-centered curriculum designed to promote wisdom and critical literacy. By helping students see and think and act and hope and design and restore and protect, we can help them live better lives in the places that are important to them. This is equity as a cause.

II. Equity as an effect is the long-tail outcome–or countless outcomes–where knowledge applied with careful scrutiny and care and affection yields itself again: Equity yields equity.

III. In public education, it is common to honor equity as a vague hope and desirable characteristic of our work as a whole–on ‘schooling,’ for example–but we might be better served to emphasize it as both an input and output for (or cause and effect of) curriculum, teaching strategies, learning models, reading lists, and countless other bits and pieces of what we do as teachers.

IV. That is, we might pursue equity and in doing so seek out opportunity, affection, justice, and knowledge.

V. Academic knowledge is to critical literacy as teaching students to saw wood is to designing and building homes.

VI. That is, critical literacy seeks equity and academic knowledge should serve critical literacy (defined here as the ability and tendency to recognize the parts of the world that need changing, and then knowing how to change them).

VII. Equity is insufficient as a singular goal for the work we do–a bare-minimum quality that precedes realizing our collective potential as a society.

VIII. For now, helping students know and tell their stories and know and change and care for their ‘places’ is part of your job as a teacher in the era of the Black Lives Movement. This has always been true but is simply now more visible.

IX. As one is wounded, we are all wounded.

X. As others become healed, we all become healed and all become healers.