Why Does It Sometimes Feel Like Parents Don’t Care?

by Terry Heick

As long as communities have no voice in—or capacity to understand—curriculum, the interaction between schools and communities will always be broken.

What a student studies should be the product of a cultural exchange that honors both local “memories” and modern contexts with an awareness of global trends. That’s it. Not textbooks and iconic academic ideas, but cultural and intellectual realities. That this may sound like crazy talk is either proof that it is crazy talk, or works to underscore the point. Either way, what families hear from schools is crazy talk, indeed.

The net result of this bias is, at best, seemingly disengaged students, apathetic parents, and disenfranchised communities. We have a system in which the only experts are the teachers, which makes it look like they’re the only ones that care.

If it’s true that teachers care way, way more than anyone else, education’s got a marketing problem.

And if it’s not true, education has a self-awareness problem.

Either way, there’s a problem.

Let’s Be Vague Together

Over time this erodes the credibility of, among other things, learning. Not education—learning. Education is borderline untouchable. We never run out of customers no matter how crazy we become. In most cities and states, laws require students to attend school to have other “perks,” like driving a car. Parents can go to jail for truancy. So whether or not parents or students understand what they’re studying or why or to what end (other than “getting a job,”) most students will show up most days.

Attendance is enforced and students are encouraged to “pass.”

We encourage “good grades.”

The end result is, hopefully, “graduation.”

This is akin to encouraging a scientist to “study stuff”—and to do it “a lot” so that eventually they can “publish.” Or an artist to “paint” or a musician to “play something.” This kind of empty phrasing is making teaching and learning a murky thing to the people we serve.

And that’s really, really bad.

The Empty Language Of Education

The language we use to teach, assess, and report student progress is artificial—and reflects an artificial system whose lack of authenticity starts with the kinds of things students learn. (Study for your test so you can get an A and pass my class and prepare for your future.)

The language families use to promote success within these artificial systems is itself artificial—and reflects a lack of understanding of how learning happens. (How are you doing in school? Make sure you do your homework. A read a lot. I’m proud of you.)

Does this make anyone else feel icky?

Schools, too often, take on design elements (of which language is a part) that serve teachers and administrators. Right now, we exchange letters, phrases, and labels in brief conversations with parents—when we can get them to show up to school to begin with.

But in truth, this isn’t about parent-teacher conferences, phone calls home, attendance on family literacy nights, or academic progress. These are relatively minor issues.

Education has retreated into a collection of policy and jargon that, while useful in self-referential contexts, ultimately mutes students, families, and communities. And while this is concerning, a larger problem is the detachment between communities and content.

The who and the what of learning.

We can barely discuss how teaching and learning happen in terms of student progress or teacher effectiveness. What chance do we have to get at the idea of people and curriculum? Who’s doing the learning, where are they from, and what are they learning?

These kinds of questions are well beyond the reach of most principals and district officials, much less teachers, students, or low-income parents that struggle to do anything shake their heads at it all. And the worst part? The inability to answer questions of academic progress or curriculum obscure the biggest question in education:

Why learn?

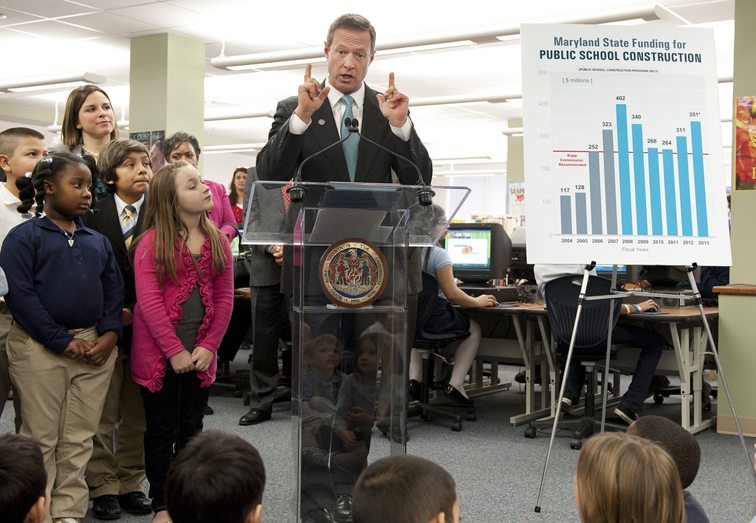

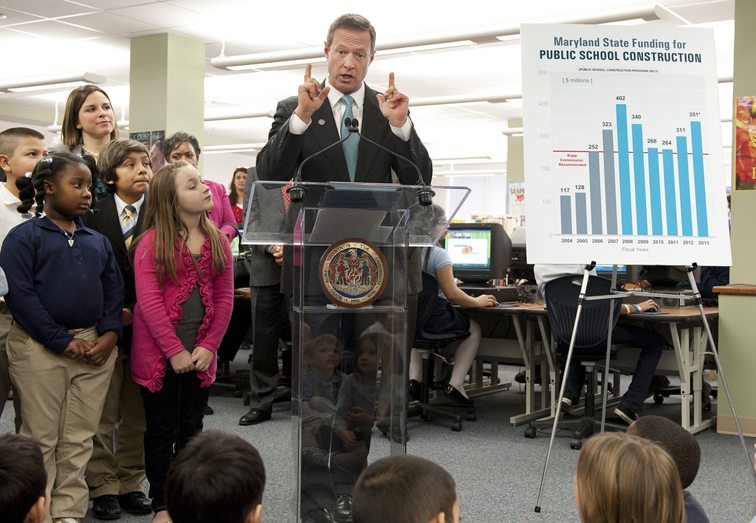

Why It Can Seem That Parents Don’t Care; image attribution flickr user mdgovpics