How Inquiry Teaching Can Help Us Through Divided Times

contributed by Drew Perkins

Educators and education, in general, are increasingly getting swept into the morass of culture wars and polemic battles playing out in our media and political processes and the downstream effects aren’t only dispiriting, they’re dangerous.

Dangerous to and for the educators trying in earnest to navigate these waters. Dangerous to and for our students who are suffering from and sometimes being drawn into the noise that continues to encroach on the academic spaces meant for teaching and learning and shared understanding. Dangerous to our democracy and the well-being of our country as the challenges to quality teaching and learning becomes ever more challenging in ways that run contrary to one of the essential characteristics that make our democracy work, inquiry.

Just as checks and balances make the US Constitution simultaneously stable and adaptable, so public checking makes the Constitution of Knowledge simultaneously stable and adaptable. —Jonathan Rauch, The Constitution of Knowledge (p. 93)

At the heart of what makes the US democratic system work well is a process of inquiry called liberal science. Jonathan Rauch expertly outlines this in his 1993 book, Kindly Inquisitors, and builds upon that work in the 2021 book The Constitution of Knowledge. In essence, liberal science is the application of inquiry, in various forms, that seeks to clarify a consensus of truth. In this pursuit, all ideas are subject to criticism with an important understanding that we separate the idea from the person.

In our schools and classrooms, the inquiry process most certainly applies differently than in the policymaking or even the culture war realm. In K12 settings educators are tasked less with creating knowledge while higher education is expressly designed for that purpose. Even still, K12 classrooms of all ages benefit greatly from the effective use of inquiry to leverage curiosity, guide thinking and learning, and to examine and evaluate, through critical thinking, important ideas.

A hypothesis worth considering is that the publication of the 1983 report A Nation At Risk which recommended, among other things, that we adopt more “rigorous and measurable standards” unintentionally set us on a course of educational reform that has contributed to our current state of affairs. This state of affairs is marked by different sets of ‘truth’, a failure of too many to interrogate ideas in good faith, and a resistance to criticism and questioning often results in placing inquirers as enemies.

The ensuing educational reform focused on accountability and test scores in ways that disincentivized and made it more difficult for teachers to engage students in what we call Rich Inquiry. In conjunction with several other factors, decades of students were left with fewer opportunities to engage in academic settings where high level inquiry was the norm and thus failed to develop those skills that would help them be better problem-solvers and resilient to ideas that they may find disagreeable.

We help schools and teachers design and deliver teaching and learning that helps students build important knowledge and understandings through the inquiry process. When teachers engage students effectively through inquiry not only will test scores be as good or better than more traditional teaching approaches (my student’s scores were), the students also learn how to engage in the kinds of thinking that are consistent with the liberal science that can help us emerge from our dangerously divided times.

There are a wealth of great resources, tools, and exercises educators can use to bolster inquiry in their practice. Our archive of inquiry-related pieces is a great starting point. Some of our favorite education-specific resources are the Right Question Institute (QFT), Project Zero, Warren Berger (Beautiful Questions), and Kath Murdoch.

I also encourage educators to engage with non-education-specific (but rich in inquiry) resources. In my recent podcast chat (Ep. 278 Bridging Divisive Conversations With Curious Inquiry) with Mónica Guzmán about her book, I Never Thought of It That Way: How to Have Fearlessly Curious Conversations in Dangerously Divided Times, I found myself practically gushing over the analogues to great teaching and learning as she unpacks specific suggestions centered on the beautiful question, “What am I missing”?

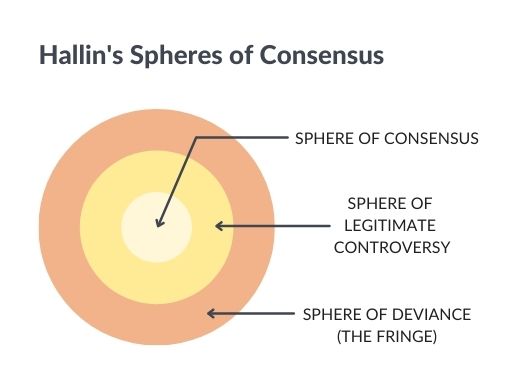

In her book, Mónica references Hallin’s Spheres of Consensus, originally used by Daniel Hallin in his book, The Uncensored War to explain the coverage of the Vietnam war. I relish the thought of using this as a frame for considering interesting questions like, for example, the one posed by the 1619 Project Education Network, “How does the story of the U.S. change if we mark the beginning of U.S. history in 1619 instead of 1776?”

I don’t agree with that assertion but I don’t have to. Consider the questions a skilled teacher could pull from students through inquiry teaching. Which spheres would this and the ensuing questions and actual facts of history land? I get excited just contemplating the discussion, thinking, and learning while simultaneously building the inquiry skills, intellectual humility, and resilience to differing ideas that are vital for success in life and for the success of our democracy.

One can easily imagine other such potentially ‘divisive’ but cognitively engaging questions to pursue. If I were back in my Government classroom and teaching about the Electoral College examining Donald Trump’s claim that he won the 2020 election could be a wonderful learning opportunity, even if uncomfortable. With younger ages such politically charged questions may not be appropriate, nor align with the course content. Still, there are myriad beautiful questions to dive into and plenty of space to practice and build those vital inquiry skills.

“Teach the Truth” seems to miss the mark on what we should expect from our schools because while it is demanding intellectual humility it can easily manifest in ways that lack it. Whose truth? Your truth? My truth? Their truth? Our truth? Teach ‘truths’ and question them all. — Drew Perkins (@dperkinsed) July 11, 2021

Whether your main concern is the false claims of ‘truth’ or that of the excesses of cancel culture limiting what you can and might do with your students, the antidote is more and better inquiry. As Rauch notes in The Constitution of Knowledge, “…when we encounter an unwelcome and even repugnant new idea, the right question to ask is “What can I learn from this?” rather than “How can I get rid of this?”

Shifting our teaching toward this approach is essential to correcting course on the predictably dangerous outcomes of a polarized and divided society that lacks these competencies.