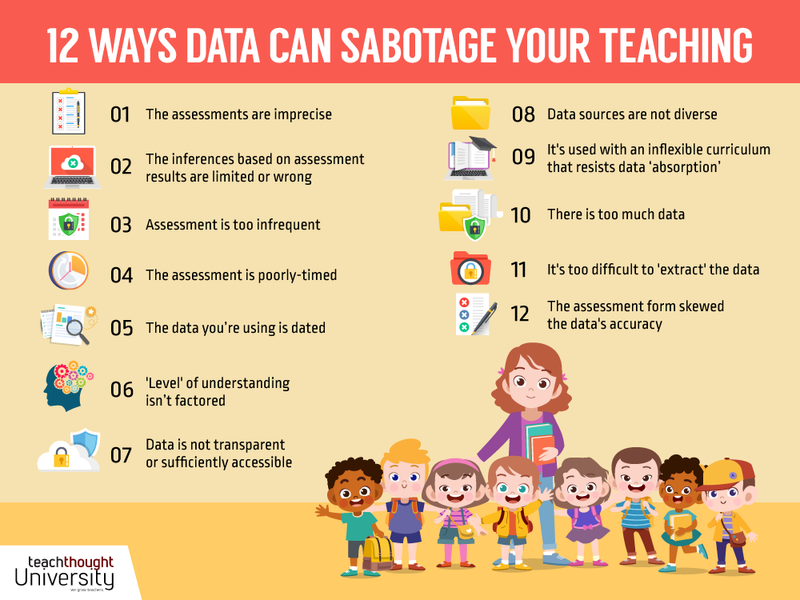

What To Avoid When Using Data To Revise Instruction In Your Classroom

by Terry Heick

How do you use data in your teaching? Or assessment?

Functionally, the purpose of assessment is to provide data to revise planned instruction. In seeing what a student understands, the best path for moving forward towards mastery can be planned based on those results—the ‘data,’ as it were.

While there are inherent (and perhaps crippling) flaws with any form of assessment (what is the best way to determine what a student understands?), assessment design is a topic for another day. For now, it can help to simply understand data better—for its benefits and perhaps more importantly, its limits.

Data champions like Rick Stiggins, Richard DuFour, and Nancy Love have done wonderful work with—and for–data. Love’s book Using Data to Improve Learning for All is a well-written and thorough starting point for any teacher wanting to better understand how data can support improvement in their craft.

But it’s not that simple.

How Is Data Used In Teaching?

Data has become not just the catalyst of school improvement, but the galvanizing force in ed reform en masse.

Broadly speaking, data is used to evaluate student mastery of specific academic standards. These ‘evaluations’ yield data that allow schools to compare students to criteria, standards, benchmarks, or other students.

See also Types Of Assessment For Learning

From No Child Left Behind, down to the data teams and professional learning communities in small rural school districts, data has been called upon to bring science—and light—to the increasingly murky waters of school improvement. In many schools and districts, data isn’t just a tool, it’s the reality everyone–and every effort–is judged by.

That which is measured is treasured (and vice-versa), and many other possibilities fall away.

While this is problematic—assessment design being so far behind available learning domains, spaces, and tools—there are ways the damage done by a data-driven frenzy can be minimized. The key is not dismissing data as a valuable teaching tool but understanding its limits in pursuit of better assessment design and data extraction practices, especially in the form of data-friendly curriculum and instructional design.

So what are some of the ways that data (an otherwise faultless concept) can sabotage your teaching?

1. The assessments are imprecise

Test, quizzes, projects, and other assessments that are high on procedural knowledge and low on an ability to uncover what a student understands about the content and standards being assessed are not only not helpful, they’re harmful to students, and barriers to learning in general.

When the test has more gravity than the learner, content, or teacher, something is out of whack.

2. The inferences based on assessment results are limited or erroneous

Even with a well-written assessment, using data in teaching is only as useful as the educator making the decisions about how to best modify planned instruction based on that data. Item analysis—going through each and every question by each and every student to make inferences about what went wrong–is a painstaking process, and is educated guessing at best.

When it’s done poorly, this is a recipe for disaster–or at least an uneven and frustrating learning experience for students.

3. Assessment is infrequent

In a climate of persistent assessment, each ‘test’ (quiz, exit slip, concept map, drawing, conversation, observation, etc.) provides a snapshot of what the student seems to understand (see #1).

But if such assessments are infrequent, the opportunities to demonstrate progress and mastery are limited. Students struggle with exams for any number of reasons that have nothing to do with content knowledge, from anxiety to simply having a bad day.

The more frequent the assessment, the better.

4. The assessment is poorly-timed

The right assessment at the wrong time is the wrong assessment. In an ideal environment, each student would get a completely personalized assessment pathway—the right content at the right time, the right assessment at the right time.

This is a challenge in a public school environment where educators may be tasked with a downright overwhelming workload of writing assessments, planning instruction, revising instruction, item analysis, data extraction, and so on.

Even in ‘data team’ environments, this can be too much to take on consistently no matter the can-do spirit of the teacher and school.

5. The data you’re using is dated

The right assessment given at the right time and even leading to the right inferences is of no help if it isn’t used right away. Understanding is perishable, growing and shrinking with experience and time. Data that is dated is spoiled milk.

6. ‘Depth of Knowledge’ isn’t factored

Most educators are well aware of the importance of depth of knowledge—Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy, for example. But if an exam isn’t written with intentional use of such ideas—from low-level recall to higher-level critical thinking strategies—the data has to be considered in that same limited light.

7. Data is not transparent or accessible to others

Teachers are asked to take on the Herculean task of marshaling dozens (or even hundreds) of students toward the mastery of dozens (or even hundreds) of learning objectives. Not only is this unrealistic, it’s damaging to both the teachers and the students.

The more that other content area teachers, administrators, parents, families, mentors, and even community members know about learner performance, the more inclusive the student support system. Obviously, this should be done with care. Student privacy concerns or communicating the wrong message to families who may not understand the significance are two of many challenges, here.

But at the very least, other teachers (and, increasingly, adaptive learning algorithms) should have access to what students do and don’t know–and thus what they do and don’t need.

8. Data sources are not diverse

From exit slips to tests, projects to computer-based assessments, self-assessments to peer-assessments, district assessments to national assessments, criterion-based to norm-referenced and otherwise, the more diverse the sources of data, the more complete macro view of understanding.

9. Inflexible curriculum that resists data ‘absorption’

If the curriculum is scripted, the pacing guides brutal, the curriculum maps rigid and static, the assessment pre-made and packaged—these factors are not conducive to absorbing and using the data in ways that immediately react to student learning needs.

10. There is too much data

Nancy Love explains in her book, ‘Using Data to Improve Learning for All‘, Love explains that, “Simply having more data available is not sufficient. Schools are drowning in data. The problem is marshaling data as the powerful force for change that they are. Without a systemic process for using data effectively and collaboratively, many schools, particularly those serving high-poverty students, will languish in chronic low performance—no matter what the pressures for accountability.”

Too much information can be worse than too little.

11. It’s difficult to extract the data

Data that ‘hides’ in the assessment form–assessment in project-based learning artifacts, for example.

12. The Assessment Form Skewed The Results

The wrong assessment type–one that is poorly matched to the learning objective and teacher use of data–is a common mistake. One example would be assessing student understanding and application of the writing process using true/false format rather than a writing sample.