What Are The Different Ways To Measure Understanding?

by Terry Heick

How do you measure what a student understands?

Not give them an assessment, score it, then use that score to imply understanding. Rather, how do you truly ‘uncover’ what they ‘know’–and how ‘well’ they know it?

Simple, Visible Ways To Check For Understanding

Before cataloging broader assessment forms and models, it is worth pausing on the most accessible teacher move: quick, visible checks for understanding.

These are not replacements for more formal or standards-based assessments. Rather, they function as early feedback loops—moment-to-moment cognitive indicators that suggest whether your instruction is making contact. In other words, they give you what summative scores almost never do: a clear, low-stakes glimpse into what students seem to understand right now.

They are especially useful when you:

- need a snapshot rather than a judgment

- want to adjust instruction within the same lesson

- do not want grades and compliance behaviors to distort what students show you

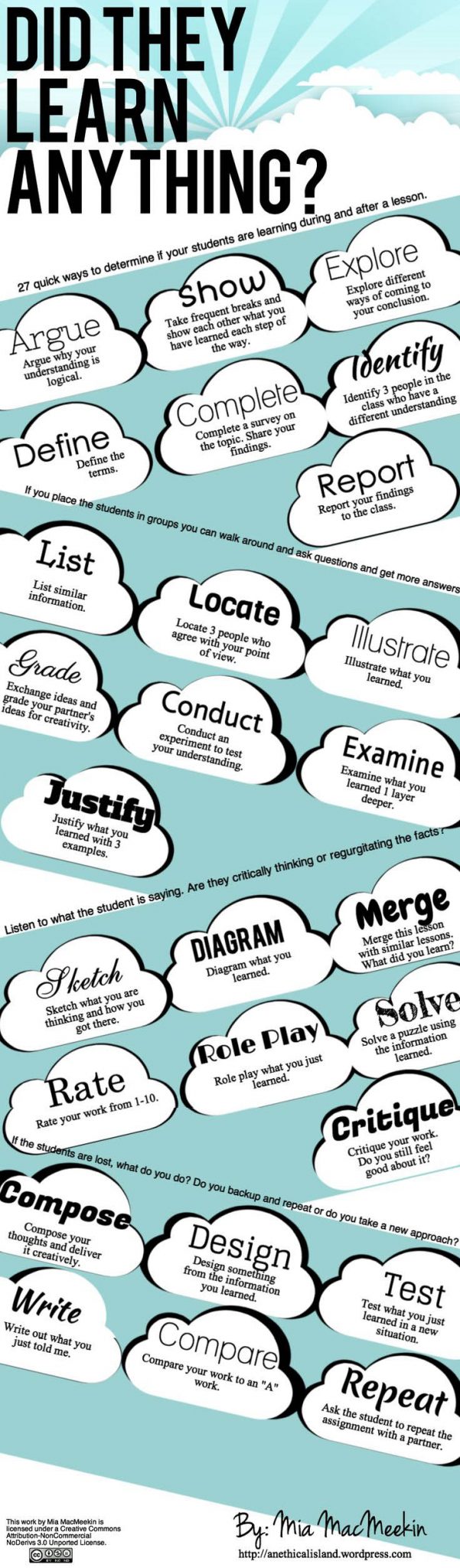

This is where Mia MacMeekin’s Did They Learn Anything? graphic is helpful. Not every suggestion on that image is quick—“test what you learned in a new situation” requires transfer and time—but many behave as thinking prompts that uncover understanding more than they measure output.

A few examples (selected because they reveal thinking rather than simply echo content):

- Restate the idea in your own words. A fast indicator of conceptual grasp rather than bare recall.

- Locate three people who agree with your position—and explain why. Agreement is not the point here; the reasoning is.

- Represent the idea visually. Students often surface misconceptions faster in a sketch, diagram, or flowchart than in a paragraph.

- Generate a question that reveals what you still do not understand. Metacognition itself becomes assessment data.

- Apply the concept in a new context. The ability (or inability) to transfer becomes a proxy for depth of understanding.

Used well, these are not “cute formative assessment tricks.” They are teacher habits for reading student cognition. And they support the larger argument of this post: we are misled when we confuse an artifact or score with understanding itself.

A Three-Layer View Of Evidence

One way to connect these simple checks to more formal assessments is to think about layers of evidence:

-

Surface Checks

Immediate indicators that students can name, restate, or briefly represent an idea (exit slips, short written responses, quick analogies, peer explanations). -

Performance Demonstrations

Attempts to do something with the idea—model it, apply it, argue with it, or solve a problem using it. -

Transfer And Meaning-Making

Evidence that learners can adapt the idea beyond its original context. This is the hardest to fake and often the most revealing.

No single check is definitive. A more reliable approach is to layer evidence over time: a surface check (“restate the claim”), a performance check (“revise this weak claim”), and a transfer check (“develop a claim for a new, unfamiliar topic”). That sequence does not make assessment perfect, but it makes it far less likely to mislead you about what students truly understand.

Simple Ways To Check For Understanding

Quick, low-stakes checks that make student thinking visible in real time.

Restate It In Your Own Words

Ask students to briefly restate a concept, process, or claim without looking at their notes.

What it shows: basic conceptual grasp beyond recall; language students naturally use to make sense of the idea.

Find Someone Who Agrees (Or Disagrees)

Students briefly share their position, then locate a peer who agrees or disagrees and articulate why.

What it shows: how students are reasoning, not just what they remember.

Sketch Or Diagram The Idea

Invite students to draw a quick diagram, timeline, or flowchart that captures how something works.

What it shows: structural understanding and common misconceptions that may not appear in text.

Ask A “Still Don’t Know” Question

Have students write a question that honestly reflects what they still do not understand.

What it shows: learners’ awareness of gaps, and where instruction may need to slow down or shift.

Use It In A New Situation

Ask students to apply today’s idea to a different text, problem, or real-world scenario.

What it shows: whether understanding is flexible or tied only to the example you used in class.

55 Ways To Measure Understanding

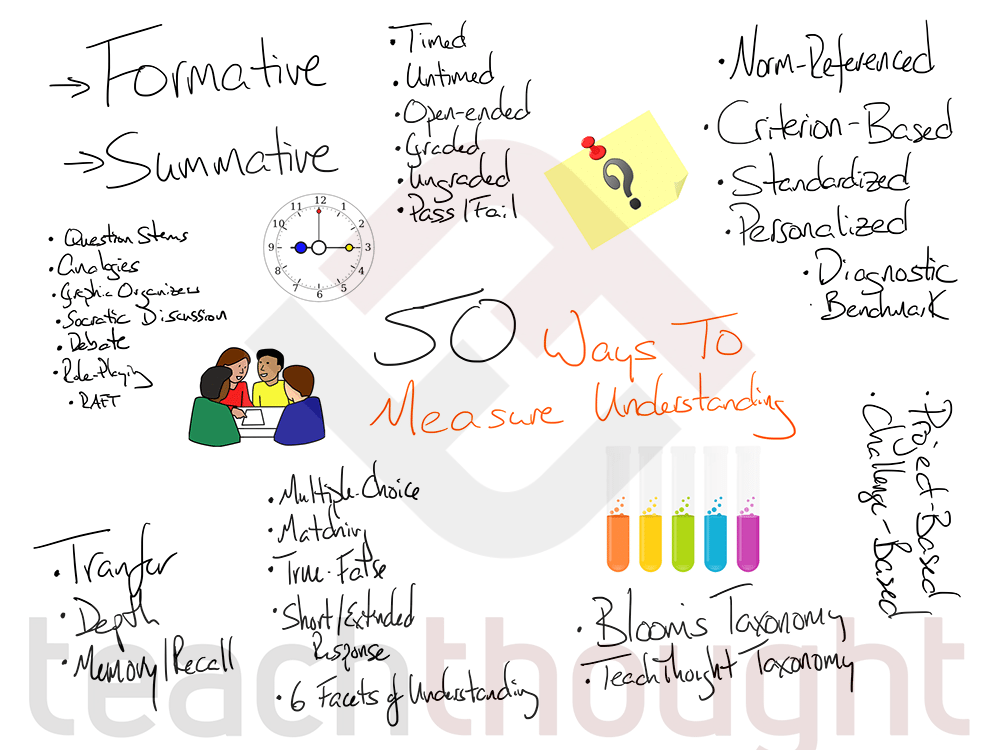

With the purpose of assessment clarified and quick checks for understanding in mind, it can be useful to see a broader landscape. Some of what follows are assessment forms (e.g., exit slips), some function as frameworks or models (e.g., Bloom’s Taxonomy), and some are more commonly thought of as teaching strategies (e.g., Socratic discussion). Each offers one more way to make understanding visible.

Assessment Forms For Measuring Understanding

These can be thought of as reasons to test or broad purposes that shape how and why we assess.

-

Norm-Referenced Assessments

Norm-referenced assessments are used to compare students to one another. The goal is not primarily to understand individual growth or mastery, but to locate a student’s performance in relation to a larger group. -

Criterion-Based Assessments

A criterion-based assessment evaluates a student’s performance against a clear, published goal or objective. In contrast to “do well on the test,” students are measured against specific performance standards tied to defined outcomes. -

Standardized Assessments

A standardized assessment uses common items, procedures, and scoring for all students. The perceived advantage is that everyone is weighed with the same instrument and there is a shared “bar” for performance. -

Standards-Based Assessment

A standards-based assessment is a kind of standardized assessment explicitly grounded in academic content standards (e.g., “Determine an author’s purpose…”). Performance is reported in relation to those standards rather than only as points or percentages. -

Personalized Assessments

Personalized assessments are designed around an individual learner’s goals, needs, or pathways. The form of the assessment may look familiar (a project, a reflection, a portfolio), but the criteria, content, or task are tailored to the student rather than fully standardized. -

Pre-Assessment

Pre-assessment occurs before formal teaching and learning begin. It can inform lesson and unit planning, grouping strategies, personalized pathways, future assessments, and even revisions to a curriculum map. -

Formative Assessment

Formative assessment occurs during the learning process and exists primarily to inform what happens next. A quiz can be formative, but so can a conversation, a draft, a misconception you notice, or a pattern in exit tickets. The key is its purpose: to shape teaching and learning while they are still in motion. -

Summative Assessment

Summative assessment is any assessment given when the teaching is considered “done.” This is often the end of a unit, course, or year. Its tone is evaluative, which is one reason why we should be careful about how often we treat assessments as truly summative. -

Timed Assessment

Any assessment that must be completed within a defined period is a timed assessment. The constraint of time shapes both the task design and the student’s performance, whether it is a ten-minute quiz or a multi-day project deadline. -

Untimed Assessment

Untimed assessments are less common in scheduled school systems but can reveal what a student knows and can do without the pressure of time. They can also be more equitable for learners who process or respond more slowly. -

Open-Ended Assessment

Open-ended assessments create space for students to demonstrate knowledge, skills, and competencies in varied ways. Autonomy, creativity, and self-efficacy play a larger role, which means student mindset becomes part of the assessment design challenge. -

Game-Based Assessment

In game-based assessment, performance within a specific rule system provides evidence of learning. This can be a digital game, a simulation, or even an athletic contest where observable performance and decision-making function as assessment data. -

Benchmark Assessment

Benchmark assessments evaluate student performance at key intervals, often at the end of a grading period. One goal is to predict performance on later, higher-stakes summative assessments. -

Group Assessment

Group assessment is conducted with students working together, often with distributed roles and responsibilities. The challenge is isolating individual understanding within social dynamics and shared products. -

Diagnostic Assessment

Sometimes used interchangeably with formative assessment, diagnostic assessment focuses on uncovering patterns in strengths, needs, misconceptions, and prior understanding to inform future teaching and learning.

Assessment Types For Measuring Understanding

These can be thought of as “types of tests” or specific formats for gathering evidence.

-

Short-Response Tests

Short written or verbal responses to questions or prompts. Useful for checking basic understanding, targeted skills, or specific pieces of content without requiring extended writing. -

Extended Responses (On-Demand Writing, Essays, etc.)

Longer written pieces—from a few paragraphs to research essays—that require students to sustain an idea, organize evidence, and demonstrate more complex thinking. -

Multiple-Choice Tests

Multiple-choice assessments can provide efficient data, but they are highly dependent on question quality and often favor strong readers and compliant test-takers. They can suggest what a student selected but not always why. -

True/False Tests

Well-designed true/false items can challenge students to attend to nuance. One variation is to have students revise a false statement until it becomes true, which can reveal misconceptions more clearly than a simple mark. -

Matching Items

Matching assessments are quick to create, complete, and score. They can be effective for vocabulary, facts, and simple relationships but rarely show depth or transfer. -

Performance And Demonstration

Here, students attempt to perform a skill or demonstrate a competency in real time—executing a pass in soccer, demonstrating the effect of gravity on orbits, or modeling how propaganda works. The performance itself becomes the evidence. -

A Visual Representation

Asking students to create a model, diagram, or symbolic representation of an idea (e.g., the water cycle, use of transitional phrases) often exposes what they understand about structure and relationships. -

Analogies

Analogies are underrated assessment tools. Students can complete analogies, revise them, explain why a given analogy is flawed, or create their own. Each move reveals how they see relationships among ideas. -

Concept Maps

Concept maps allow learners to position and connect key ideas. The arrangement, labels, and links provide insight into how students organize and prioritize what they know. -

Graphic Organizers

Graphic organizers can function as pre-writing tools, planning tools, or assessment artifacts. Completed organizers (Venn diagrams, cause-effect chains, etc.) provide visible evidence of understanding and misconception. -

A Physical Artifact

A product, model, prototype, display, or other physical artifact can serve as evidence of understanding. The key is designing criteria that separate appearance from real conceptual or procedural knowledge. -

A Question

A student asking or refining a question can function as assessment. The quality, focus, and depth of the question reveal as much about understanding as many traditional test items. -

A Debate

Structured debate allows students to surface claims, evidence, counterclaims, and rebuttals. Observation of how they listen and respond can be as important as the positions themselves. -

Conversation, Group Discussion, Socratic Discussion

Conversations and Socratic discussions generate rich, real-time evidence of understanding. The challenge is documenting and interpreting that evidence in fair and usable ways. -

Question Stems

Providing stems for students to complete (“Why do you think…,” “What might happen if…”) can scaffold deeper responses. Students can also create stems and use them to quiz one another. -

Role-Playing

Role-play (e.g., embodying historical figures or scientific phenomena) requires students to act from within an idea rather than merely describe it from the outside. -

Question Formulation Technique (QFT) Sessions

Structured question-generation protocols like QFT can serve as assessment. The kinds of questions students ask, and how they refine them, reveal both curiosity and understanding. -

Observable Metacognition

Inviting students to think aloud about how they are thinking, deciding, or solving can produce powerful assessment data. Here you are, in effect, “assessing the thinking about the thinking.” -

Self-Assessment

Self-assessment asks students to evaluate their own understanding against clear criteria. Used well, it can strengthen ownership and provide data that external observations might miss. -

Peer Assessment

Peer assessment brings students into the feedback process. It can increase the amount of feedback in the room and support a more communal sense of quality and revision. -

Expert Assessment

Panels, juries, and other forms of expert review (from science fairs to talent shows) can provide specific, often narrow feedback based on expertise. The risk is that the criteria may not be transparent to students. -

RAFT Assignments

RAFT (Role–Audience–Format–Topic) reframes a task by changing who is speaking, to whom, in what form, and about what. This can force students to think more critically about content, audience, and purpose. -

A Challenge

Designing a challenge for students to complete (often with gamified elements) can serve as assessment. Success or struggle within the challenge provides evidence of understanding and persistence. -

Teacher-Designed Projects

Projects designed by the teacher create a relatively controlled way for students to produce something that should, in theory, reflect understanding. The product becomes a proxy for learning, for better or worse. -

Student-Designed Projects

When students design the project with or without the teacher, they often learn different things in different ways. This can be powerful but also confusing if your assessment criteria are narrow or rigid. -

Self-Directed Learning

Supporting students to plan, manage, and document their own learning experiences over time creates a kind of open-ended assessment. The arc of their decisions and products becomes the evidence.

Frameworks And Models For Measuring Understanding

These are ways to frame thinking about understanding rather than specific test formats.

-

Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bloom’s original and revised taxonomies describe levels of cognitive work—remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, create. Assessment tasks can be aligned to different levels to better match the kind of understanding you hope to see. -

The TeachThought Learning Taxonomy

The TeachThought Learning Taxonomy reframes learning around transfer, self-direction, and meaningful inquiry. It can be used to design and evaluate assessments that move beyond recall toward more durable, flexible understanding. -

UbD’s Six Facets Of Understanding

In Understanding by Design, Wiggins and McTighe describe six facets—explain, interpret, apply, have perspective, empathize, and have self-knowledge. Each facet suggests different kinds of assessment evidence. -

Marzano’s New Taxonomy

Marzano’s framework organizes learning into three systems (self, metacognitive, cognitive) and a knowledge domain. It can guide the creation of assessments that consider motivation, strategy use, and content knowledge together. -

Assessing Transferability

Rather than only testing recall in the same context in which something was taught, transfer-focused assessments examine how well students can use what they know in new or less supported situations. -

Graded Assessments

Most formal school assessments are graded. The grade can be useful as a communication tool but can also distort motivation, take time to compute, and obscure the more nuanced story the underlying evidence might tell. -

Ungraded Assessments

Ungraded assessments foreground feedback and revision. They are often better aligned with the primary purpose of assessment: to inform learning and teaching rather than to sort or rank students. -

Feedback-Only Assessments

Feedback-only assessments go a step further, intentionally limiting communication to comments, suggestions, and questions. The emphasis is on growth toward mastery rather than on documenting performance with a score. -

Pass/Fail Assessments

In pass/fail assessment, the primary question is whether a standard was met. Letter grades and points may be absent entirely. The tone shifts from “How well did you perform?” to “Did you reach the bar?” -

An Ongoing Climate Of Assessment

A climate of assessment treats assessment as a continuous, playful, and formative part of the learning environment. Critical ideas and skills are revisited across time, contexts, and formats rather than captured in a single high-stakes moment. -

Snapshot Assessments

A snapshot assessment captures what a student appears to know at a single moment in a specific format. Snapshot data can be misleading if it stands alone but becomes more useful when connected to other evidence over time. -

Measurement Of Growth Over Time

Growth-oriented assessment looks less at where students end up and more at how far they have come. Approaches like grading backward can make it harder for students to “fail” in traditional ways and easier to see individual progress. -

Concept Mastery

Concept mastery focuses explicitly on understanding the ideas themselves rather than primarily on performance of skills. This can be useful when troubleshooting where a breakdown is occurring. -

Competency And Skill Mastery

Competency-based assessment zooms in on what students can actually do. Separating concept mastery from skill mastery can make remediation more precise and less discouraging for learners.

Summary Table: Assessment Forms And Their Primary Purposes

| Form | Primary Purpose | Typical Question It Answers |

|---|---|---|

| Norm-Referenced | Compare students to one another. | “Where does this student sit relative to the group?” |

| Criterion-Based | Measure performance against a clear goal or standard. | “Did the student meet this specific objective?” |

| Standards-Based | Report learning in relation to content standards. | “How close are they to mastery of this standard?” |

| Pre-Assessment | Map prior knowledge and misconceptions. | “Where should we begin, and what do we need to revisit?” |

| Formative | Shape what happens next in teaching and learning. | “What should we do tomorrow based on today?” |

| Summative | Evaluate performance after instruction is considered complete. | “What did the student demonstrate by the end of this unit or course?” |

| Benchmark | Monitor progress at key points and predict later performance. | “Are we on track for the end-of-year goals?” |

| Diagnostic | Identify patterns in strengths, needs, and misconceptions. | “What exactly is helping or hindering this learner right now?” |

Summary Table: Layers Of Evidence And Example Strategies

| Evidence Layer | Example Strategies | What It Mostly Reveals | Design Caveat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Checks | Restatements, exit slips, short-response questions, quick matching items. | Basic recall and first-pass comprehension. | Easy to over-interpret; students can appear to understand more deeply than they do. |

| Performance Demonstrations | Projects, debates, role-plays, visual models, performance tasks, game-based assessments. | How students use ideas, skills, and strategies in practice. | Product quality can hide the role of support, group dynamics, or templates. |

| Transfer And Meaning-Making | New-context applications, RAFT tasks, self-directed projects, cross-disciplinary challenges. | Flexibility of understanding; whether learning holds outside the original unit or example. | Difficult to design and score; requires patience and tolerance for varied, uneven products. |