The 40/40/40 Rule: An Overview

by Terry Heick

I first encountered the 40/40/40 rule years ago while skimming one of those giant (and indispensable) 400 page Understanding by Design tomes.

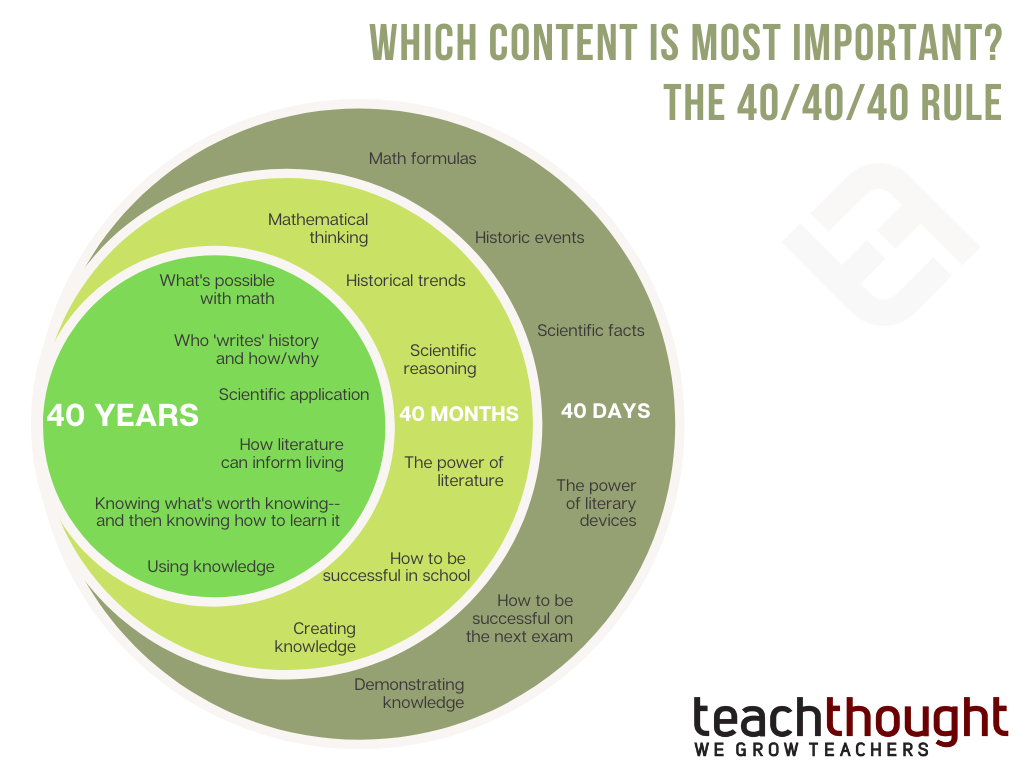

The question was simple enough. Of all of the academic standards, you are tasked with ‘covering’ (more on this in a minute), what’s important that students understand for the next 40 days, what’s important that they understand for the next 40 months, and what’s important that they understand for the next 40 years?

As you can see, this is a powerful way to think about academic content.

Of course, this leads to the discussion of both power standards and enduring understandings, curriculum mapping, and instructional design tools teachers use every day.

But it got me thinking. So I drew a quick pattern of concentric circles–something like the image below–and started thinking about the writing process, tone, symbolism, audience, purpose, structure, word parts, grammar, and a thousand other bits of ELA stuff.

Not (Necessarily) Power Standards

And it was an enlightening process.

First, note that this process is a bit different than identifying power standards in your curriculum.

Power Standards can be chosen by looking at these standards that can serve to ‘anchor and embed’ other content. This idea of “40/40/40” is more about being able to survey a large bundle of stuff and immediately spot what’s necessary. If your house is on fire and you’ve got 2 minutes to get only as much as you can carry out, what do you take with you?

In some ways, it can be reduced to a depth vs breadth argument. Coverage versus mastery. UbD refers to it as the difference between “nice to know,” “important content,” and “enduring understandings.” These labels can be confusing–enduring versus 40/40/40 vs power standards vs big ideas vs essential questions.

This is why I loved the simplicity of the 40/40/40 rule.

It occurred to me that it was more about contextualizing the child in the midst of the content, rather than simply unpacking and arranging standards. One of UbD’s framing questions for establishing ‘big ideas’ offer some clarity:

“To what extent does the idea, topic, or process represent a ‘big idea’ having enduring value beyond the classroom?”

The essence of the 40/40/40 rule seems to be to look honestly at the content we’re packaging for children, and contextualize it in their lives. This hints at authenticity, priority, and even the kind of lifelong learning that teachers dare to dream about.

Applying The 40/40/40 Rule In Your Classroom

There’s likely not one single ‘right way’ to do this, but here are a few tips:

1. Start Out Alone

While you’ll need to socialize these with team or department members soon, it is helpful to clarify what you think about the curriculum before the world joins you. Plus, this approach forces you to analyze the standards closely, rather than simply being polite and nodding your head a lot.

2. Then Socialize

After you’ve sketched out your thinking about the content standards you teach, share it–online, in a data team or PLC meeting, or with colleagues one afternoon after school.

3. Keep It Simple

Use a simple 3-column chart or concentric circles as shown above, and start separating the wheat from the chaff. No need to get complex with your graphic organizer.

4. Be Flexible

You’re going to have a different sense of priority about the standards than your colleagues. These are different personal philosophies about life, teaching, your content area, etc. As long as these differences aren’t drastic, this is normal.

5. Realize Children Aren’t Little Adults

Of course, everyone needs to spell correctly, but weighing spelling versus extracting implicit undertones or themes (typical English-Language Arts content) is also a matter of realizing that children and adults are fundamentally different. Rarely is a child going to be able to survey an array of media, synthesize themes, and create new experiences for readers without being able to use a verb correctly. It can happen, but therein lies the idea of power standards, big ideas, and most immediately the 40/40/40 rule: One day–40 days. 40 months, or even 10 years from now–the students in front of you will be gone–adults in the “real world.”

Not everything they can do–or can’t do–at that time will be because of you no matter how great the lesson, assessment design, use of data, pacing guide, or curriculum map. But if you can accept that–and start backward from worst-case “if they learn nothing else this year, they’re going to know this and that–then you can work backward from those priorities.

Those content bits that will last for 40 years–or longer.

In your content area, on your curriculum map, pacing guide, or whatever guiding documents you use, start filling up that little orange circle first and work backward from there.

Which Content Is Most Important? The 40/40/40 Rule