What Do Teachers Need To Know About The Future Of Education?

by Terry Heick

This post has been updated and republished from a 2015 article

It’s tempting to say that no matter how much technology pushes on education, every teacher will always need to know iconic teacher practices like assessment, curriculum design, classroom management, and cognitive coaching.

This may end up being true–how education changes in the next 20 years is a choice rather than the inevitable tidal wave of social and technological change it’s easy to sit back and wait for. Think of the very limited change in education since 2000 compared to the automotive industry, computer industry, retail consumer industry, etc. Huge leaps forward are not a foregone conclusion.

But it’s probably going to be a bit different than that. There are certain areas where significant change is more probable than others. It doesn’t seem likely that eLearning–as we now understand and use the term–will replace schools and teachers. Asynchronous learning–today, anyway–lacks too much to completely supplant teachers and schools. (Blended learning is more likely to be the norm in the next decade.)

See also Types Of Blended Learning

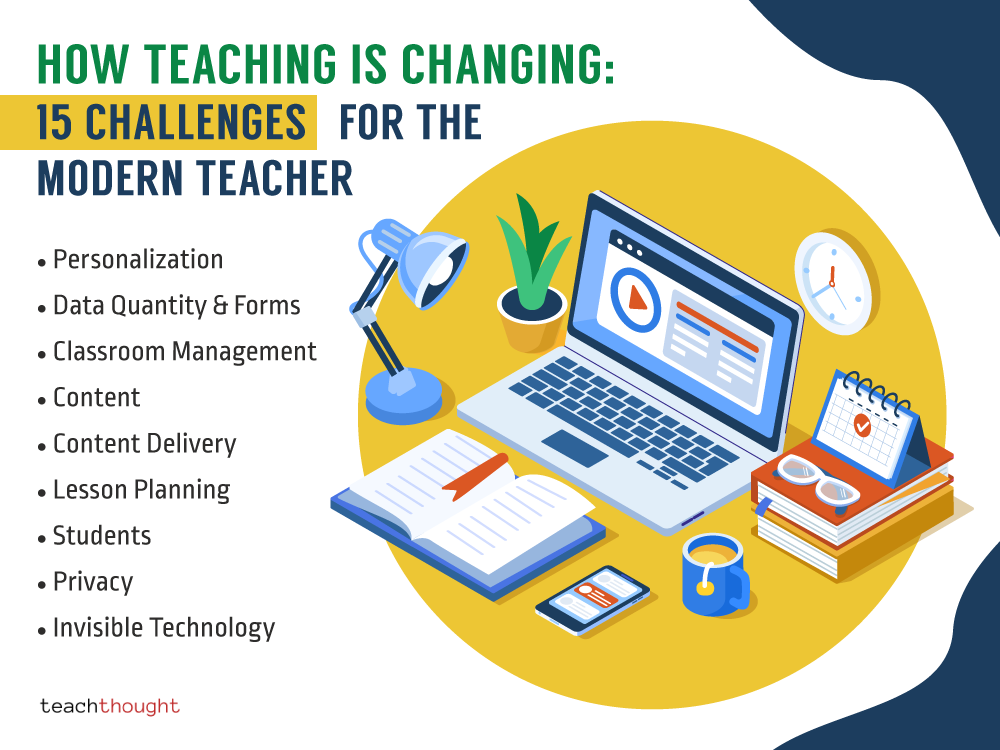

We’ve written before about the kinds of ‘things’ modern teachers must be able to do. Below are 15 tasks that are less skill-based–and some a bit more conceptual, collectively representing how teaching is changing.

Teaching is no longer about classroom management, testing, and content delivery.

How Teaching Is Changing: 15 New Realities Every Educator Faces

1. Personalization

The Old: Administer assessment, evaluate performance, report performance, then–maybe–make crude adjustments the best you can

The New: Doing your best to identify, prioritize, and evaluate data for each student individually–in real-time

The Difference: Precision

Summary

Or rather, determine the kind of data is most important for each student, figure out a way to consistently obtain that kind of data, and then either analyze it personally or monitor the algorithms that are doing it for you.

This is not unlike an automotive mechanic moving carburetors to fuel-injection systems (that are no themselves becoming outdated) in the 1980s and 1990s. The former was crude, requiring frequent corrections and ‘tune-ups’ done by hand; the latter was far more precise and required new skills on the part of the mechanic. Rather than making mechanical adjustments, mechanics became system managers. That is, they spent more time adjusting the systems–sensors, ECUs, etc–that themselves were making the adjustments.

2. Data Quantity & Forms

The Old: Numbers, letters, and maybe a bar graph or pie chart

The New: Probes, Color-coded data charts, national-level criterion-based assessment, norm-referenced local data results, placement exams, formative assessment data

The Difference: Meaning & accessibility

Summary

More and more, teachers have to design data sources and visualizations—usable data applied meaningfully. The days of taking a test and waiting for results have been gone for years. Soon it will be time to put behind us the process of even instant data results unless that data is packaged in a way that promotes seamless revision of curriculum, assessment, and instruction.

Or pushed further, which content a student encounters, when; which community they connect with, when; which level of ‘cognitive intensity’ they reach, when. Take the following data visualization for example.

“In this example, Deb Roy’s team captures every time his son ever heard the word water along with the context he saw it in. They then used this data to penetrate through the video, find every activity trace that co-occurred with an instance of water and map it on a blueprint of the apartment. That’s how they came up with wordscapes: the landscape that data leaves in its wake.”

Tomorrow’s teachers will then need to make important decisions about the kinds of metrics taken (see above) and the way it is visualized so that important patterns, trends, and possibilities are highlighted.

3. Classroom Management

The Old: Minimize negative interactions (fighting, bullying, etc.) and promoting compliance with rules and ‘expectations’

The New: New forms of ‘bullying’, online safety and privacy concerns, analyze and sometimes even coordinate student social interactions

The Difference: Scale

Summary

This could mean physical communities or digital. Teachers need to mobilize students, whether within classrooms, schools, and on campuses, or within local communities in a place-based learning or project-based learning scenario. Teaching digital citizenship, connectivity, and possibility will be more important than teaching content.

This is a reality faced today, not tomorrow.

4. Teaching

The Old: Delivering content shaped for universal consumption

The New: Coaching, guiding, supporting, and communicating with students as they navigate content and data

The Difference: Truly valuing how students think

Summary

Today’s teacher has to demonstrate for students not how to solve problems, but why those problems should be solved. It will be less about creating a PBL unit where students clean up a local creek or park, but rather teaching the students how to identify and work through those needs themselves. This is the human element of affection–honoring the things and spaces around you as a way of living.

The same goes for curiosity–thinking-aloud through self-reflection. Challenging student assumptions through digital commenting or face-to-face interactions–and connecting them with communities that can do the same.

5. Content

The Old: Initially it was teaching ‘a class,’ and then it became a list of standards

The New: Reconcile hundreds of academic standards–standards that include technology, citizenship, literacy, etc. This goes way beyond ‘content areas’ and is obviously not ideal

The Difference: Quantity

Summary

This means not just knowing the standard, planning for its mastery, and then ‘teaching’ it, but reconciling discrepancies ‘horizontally’ within and across content areas, and then ‘vertically’ across grade levels as well. And further, it’s no longer just about your class or content area, but also standards from a dozen other organizations that all chime in with well-intentioned but ultimately unsustainable to-do lists.

6. Lesson Planning

The Old: Manage grouping, finishing classwork, and creating a ‘system’ for homework

The New: Personalizing workflows based on constantly changing circumstance (data, need to know, student interest, changes in community, etc.) using flipped classrooms, digital distribution, and even self-directed learning while coordinating with a PLC

The Difference: Connectivity and interdependence

Summary

Given local context and circumstance–technology, bandwidth, social opportunities and challenges, etc–what kind of workflow is most efficient for this student?

Does it make sense to embed every student in every local community? Does it make more sense here and less sense there?

Given local literacy habits and access, is it better to spend more time gathering sources, evaluating sources, or sharing sources? What kind of adjustments should we make based on what we know about the world the students are growing up in?

Does in-person mentoring make sense, or given topics of study–agriculture, robotics, literature, music, etc.–do digital spaces make more sense?

For this student, right here, right now, what exactly do they need?

7. Your Students

The Old: Receiving a class roster

The New: Seeing 30 (or more) individual human beings, individual data sets, individual challenges and opportunities

The Difference: Becoming a more human process

Summary

This brings us to #6 (which really is kind of the point of it all)–taking all of the mechanical and gadget-borne stuff above and making it ‘whole’ for the person standing in front of you. This is not new, but the complexity of making this possible on a daily basis is.

Other New Realities The Modern Teacher Faces

8. Designing learning experiences that carry over seamlessly between home and school. So, making ‘school’ disappear and even giving the illusion that you’re working yourself out of a job.

9. Troubleshooting technology, including cloud-based issues, log-in info, etc.

10. Verifying student privacy/visibility across scores of monitored and unmonitored social interactions per week; Validate legal issues, copyright information, etc.

11. Refining driving questions and other matters of inquiry on an individual student basis

12. Insisting on quality–of performance, writing, effort, etc.–when the planning, technology, and self-reflection fail

13. Evaluating the effectiveness of learning technology (hardware, software, and implementation of each)

14. Filtering apps based on function, privacy, operating system, cost, complexity, ongoing maintenance, etc.

15. Clarifying and celebrating learning, understanding, mistakes, progress, creativity, innovation, purpose, and other abstractions of teaching and learning on a moment by moment basis

How Teaching Is Changing: 15 New Realities Every Educator Faces; image attribution flickr user nasagoddard