What Is The Difference Between Pedagogy, Andragogy, And Heutagogy?

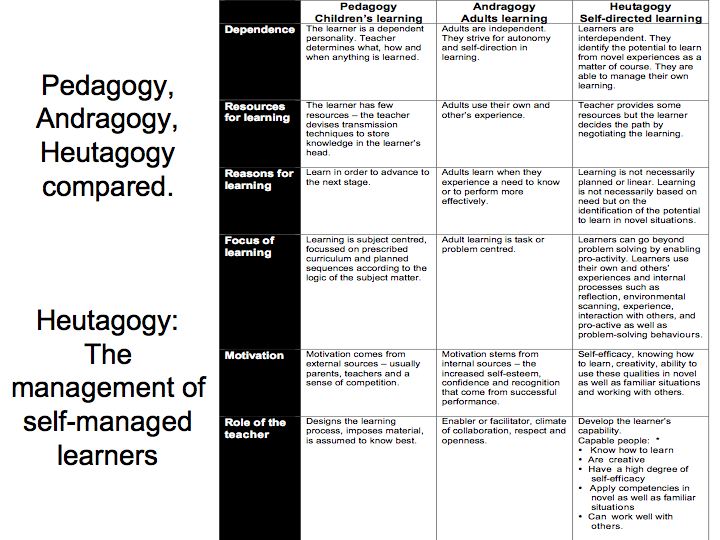

Jackie Gerstein’s work on Education 3.0 and mobile learning has helped many teachers see how shifts in technology and culture change what it means to teach. Her framing of pedagogy, andragogy, and heutagogy gives us a simple way to talk about who decides what is learned, how it is learned, and why it matters.

These terms show up in conversations about student agency, self-directed learning, and the future of schooling. For K–20 educators, they are useful not as labels to memorize but as lenses for designing tasks, units, and entire courses that gradually move learners toward more ownership of their learning.

Quick Definitions

- Pedagogy: Teaching where the goals, content, and methods are primarily decided by institutions and teachers.

- Andragogy: Teaching that is designed for adults and assumes they bring prior experience, motivation, and a need for relevance.

- Heutagogy: Learning that is self-determined, where learners co-design or fully design what they learn, how they learn, and how they will show their learning.

In practice, most classrooms blend these approaches rather than using only one. The question is not which term is “right,” but which mix best fits your students, your context, and your goals for their long-term independence.

1. What Pedagogy Looks Like In The Classroom

Pedagogy is often used as a general word for “teaching,” but here it describes more traditional, teacher-directed models. The teacher or institution specifies the standards, content, and sequence, then plans lessons to help students reach those goals.

Common features

- Curriculum is organized and mandated outside the classroom.

- The teacher selects most of the texts, tasks, and assessments.

- Students have limited voice in what they learn, although they may have some voice in how they complete tasks.

Pedagogy in practice: examples

- Elementary: The teacher selects a shared read-aloud, pre-teaches vocabulary, leads a guided discussion, and checks for understanding with a short exit ticket.

- Middle school: A science teacher designs a lab to illustrate the law of conservation of mass. Students follow a provided procedure and answer structured questions.

- High school: An English teacher chooses a core novel, builds a unit around key standards, and provides a common essay prompt to all students.

- Higher education: A professor designs a syllabus, lecture sequence, and set of assignments for a survey course. Students choose topics within those assignments but not the overall goals.

Pedagogy is often connected to content coverage and to external accountability. It is not inherently “bad” or “old,” but when used alone it can limit opportunities for students to practice the skills of self-directed learning. For more on how learning theory connects to these roles, see The Difference Between Constructivism And Constructionism.

2. What Andragogy Looks Like In The Classroom

Andragogy is usually associated with adult learning. Malcolm Knowles described adults as more self-directed, experience-rich, and motivated by relevance. In practice, andragogy assumes that learners:

- Bring prior experiences that should be used as resources.

- Need to understand why a topic matters to their lives and goals.

- Benefit when they help plan learning activities and timelines.

Andragogy in practice: examples

- Upper secondary: In a career and technical course, students identify a career interest and choose which industry certifications to pursue within a structured program.

- Dual credit / college: In a statistics course for future teachers, students analyze real classroom data and design interventions for learning difficulties they care about.

- Graduate / professional learning: Participants co-create part of the syllabus by proposing case studies from their own classrooms and selecting which ones to investigate together.

Many K–12 classrooms incorporate andragogical elements, especially in project-based units where students choose topics, products, or audiences. For a broader overview of how self-direction develops, see What Is Self-Directed Learning?.

3. What Heutagogy Looks Like In The Classroom

Heutagogy is often described as self-determined learning. The focus is less on delivering content and more on helping learners design their own pathways, generate questions, locate resources, and decide how to demonstrate growth.

Common features

- Learning goals are negotiated or generated by learners.

- Assessment is flexible and often co-designed.

- The teacher’s role shifts from “provider of content” to “coach, co-learner, and connector of resources.”

Heutagogy in practice: examples

- Upper elementary / middle school: Students design personal inquiry projects where they select a question, plan how they will investigate it, and document their learning in a learning journal.

- High school: In a media literacy course, students choose a real community issue, decide what they want to learn about it, and create a product (podcast, video essay, curated resource hub) to share their findings.

- Higher education / teacher preparation: Candidates in a methods course co-design a unit that addresses both program outcomes and their own professional growth goals, using a Self-Directed Learning Model as a guide.

Heutagogy often overlaps with Education 3.0 ideas, where learners are creators and connectors rather than just recipients of content. For an example of how this is framed in a broader conversation about technology and learner roles, see Education 3.0: Where Students Create Their Own Learning.

Putting Pedagogy, Andragogy, And Heutagogy On A Continuum

One way to think about these terms is as a continuum of control and agency in the learning process.

- Pedagogy: Teacher and institution decide what students will learn and how they will learn it.

- Andragogy: Adults’ needs, goals, and experiences shape how content is taught and how learning is organized.

- Heutagogy: Learners decide what to learn, how to learn, and how to show what they know, with the teacher and community as resources.

In most K–20 settings, you might start with more pedagogical structures, introduce andragogical elements as students gain skill and confidence, and gradually create space for heutagogical experiences. Classroom culture matters here. For practical strategies, see Tips To Promote A Self-Directed Classroom Culture.

If you are exploring how theories, models, and frameworks fit together, the overview of key learning theories at Learning Theories: Definitions and Examples can provide additional context.

FAQ: Common Questions About Pedagogy, Andragogy, And Heutagogy

Can children learn in an andragogical or heutagogical way?

Yes, with support. Younger learners often need more structure, but they can still make meaningful choices about topics, questions, and products. For example, in a project-based unit, you might keep core standards and time frames (pedagogy) while allowing students to choose the focus of their project and how to present it (andragogy and early heutagogy).

Is pedagogy “wrong” for teaching adults?

Not necessarily. Adults sometimes prefer clear direction, especially when learning high-stakes content in limited time. The key is to be intentional. If your adult learners are capable of more self-direction than the course design allows, you may be underusing their experience and motivation. When possible, invite them into goal-setting, task design, and reflection.

How do learning theories like constructivism relate to these terms?

Constructivism and constructionism describe how learning happens, while pedagogy, andragogy, and heutagogy describe how learning is organized and who makes key decisions. A classroom can be constructivist in spirit while still being mostly pedagogical in structure. For a deeper look at these theories, see The Difference Between Constructivism And Constructionism.

How can I start moving toward more heutagogical practice?

A practical starting point is to build small, recurring structures where students plan, monitor, and reflect on their learning. Regular learning journals, negotiated success criteria, and co-designed inquiry questions are all manageable entry points. Over time, you can increase the level of choice and co-design as students demonstrate readiness.

Key Takeaways For K–20 Educators

- Use pedagogy when learners need more structure, explicit modeling, and carefully sequenced content.

- Draw on andragogy when learners bring experience, clear goals, and a need for relevance that should shape how you teach.

- Experiment with heutagogy when you want students to practice designing their own learning, especially in capstone projects, passion-based inquiries, or advanced courses.

Over a year, or across a program, you can gradually shift the balance from pedagogy toward andragogy and heutagogy so that students leave not only knowing more, but also better able to direct their own learning beyond your classroom.

References

- Knowles, M. S. (1980). The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Cambridge Adult Education.

- Hase, S., & Kenyon, C. (2000). From andragogy to heutagogy. Ultibase, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology.