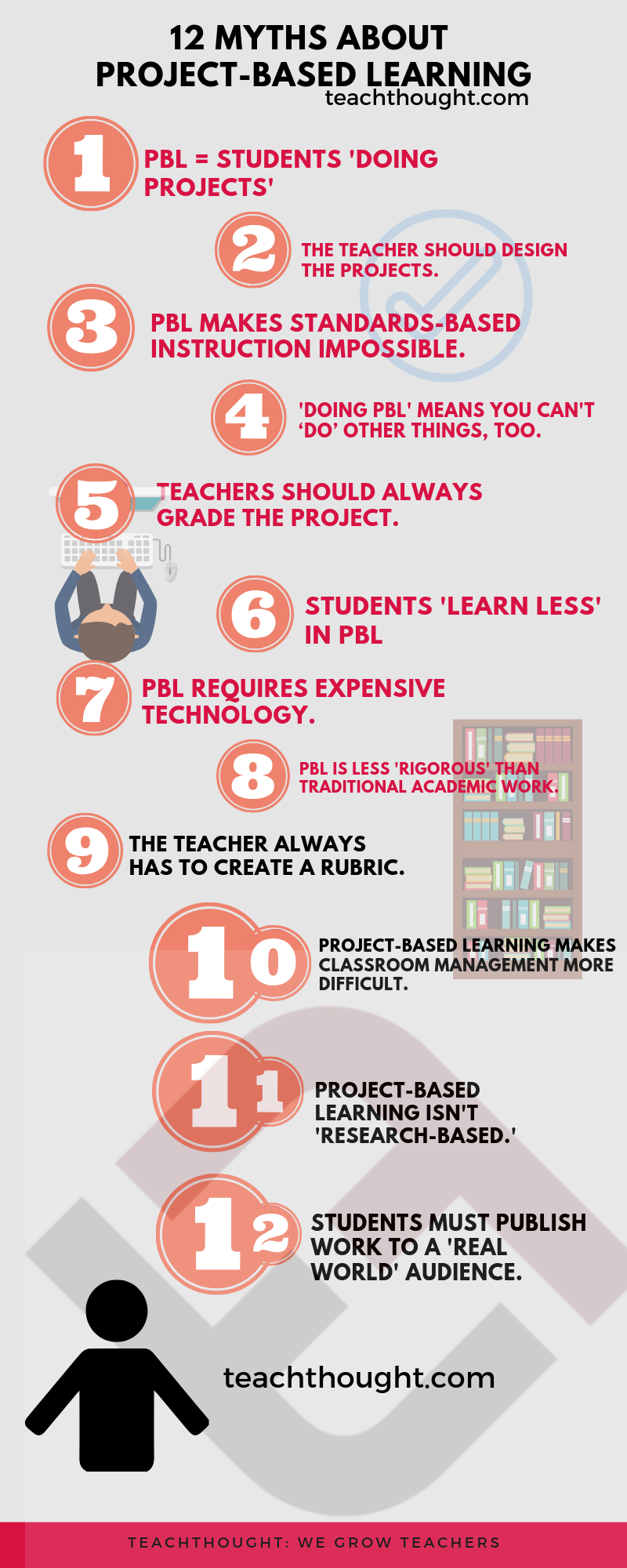

What Are The Greatest Myths About Project-Based Learning?

Simple premise: What are the most common myths about project-based learning? Put another way, what do we misunderstand about PBL that keeps it from realizing its full potential?

At TeachThought, we’re proponents of project-based learning as one of countless progressive learning models that can grow teachers–and thus grow the minds and potential of students.

We’d thought it’d be useful to examine the myths around project-based learning that may keep it from more widespread adoption or precise integration across K-12+ education worldwide.

12 Of The Most Common Myths About Project-Based Learning

1. Myth: Project-Based Learning = students doing projects

Among the most pervasive myths about project-based learning is that students ‘doing projects’ equates to students learning through PBL.

While it’s unlikely students can complete projects without learning anything, project-based learning emphasizes the process of learning through the design and execution of projects. Put another way, students would certainly ‘be learning’ by completing projects, but it wouldn’t be ‘project-based learning’ because the focus would be on the project and not the learning.

It’s project-based learning not ‘learning-based projects.’

Planning, researching, collaboration, problem-solving, iterating, pivoting, publishing, and other ‘PBL verbs’ (that is, cognitive tasks commonly required to complete projects in PBL) all require ownership as well as creative and critical thinking on the part of the students, but to truly shine, PBL ideally focuses on learning as a process and growth over time while the projects provide artifacts of that process and growth to reflect on, curate, and symbolize human achievement (versus ‘student’ achievement).

You can read more about the difference between doing projects and project-based learning.

2. Myth: The teacher should design the projects.

Teachers can design the projects—or components of the projects like the timeline, graded assignments, checkpoints, collaborations, purposes and audiences, etc., but ideally, teachers and students work together, supported by relevant experts, community members, and families to lead the learning process over time—and how the students see themselves along the way.

3. Myth: Project-Based Learning makes Standards-Based Instruction difficult/impossible.

Standards-based instruction is an approach to teaching that places the content itself (in the form of academic standards) at the center of the learning process (through backward-design, for example).

This approach to teaching has been part of the foundation of modern education reform, where educators become very clear about standards and ‘what they say’ (often through learning targets), then design assessments around exactly those standards, then systems of grading that are also standards-based. (See also project-based learning ideas.)

If you’re going to focus in earnest on mastery of academic standards, project-based learning seems like a curious fit—and I’d have to agree. If you’re all about the content, there may be better approaches for student work, learning, and growth than PBL (though this is subjective as well). If, however, you’re interested in helping grow students that are able to consistently transfer knowledge and competencies from your classroom to the lives they live and the future they see (or have trouble seeing), project-based learning is worthy of your own scrutiny and understanding as a professional educator.

Exactly how to align standards and PBL isn’t always cut-and-dry, but neither is direct instruction, RTI, ability grouping, mixed ability grouping, reciprocal teaching, literacy instruction—or really anything else a school and teacher work hard to do on a daily basis to help children grow. It’s all difficult.

Which brings us to myth #4…

4. Myth: ‘Doing PBL’ means you can’t ‘do’ other things, too.

This is one of the more problematic myths about project-based learning, mainly because it can discourage teachers and/or schools from using it altogether.

From literacy plans to 1:1 programs, Google Classroom to Competency-Based Learning, brain-based teaching to team-building and, inquiry, or critical thinking, no matter what ‘your school is focusing on,’ there are few ‘efforts’ in schools that are would disallow PBL. Because PBL is primary a way to frame curriculum and the work students will be doing in pursuit of its mastery, it doesn’t have to be an either/or proposition.

In fact, focusing on ‘one program at a time’ itself is a curious way to seek school improvement and student achievement. If you’re going to truly focus on one thing, it should be the improving the lives of students. Everything else can work backward from there.

5. Myth: Teachers should always grade the project.

While you obviously can grade the project, project-based learning is learning through the design and ongoing execution of multi-faceted projects.

If you believe that the student would benefit from grading the final product or artifact (assuming there is one), grade it.

If oral/narrative feedback from you makes more sense, do that.

If feedback from someone in the community or a content expert makes more sense, do that.

Do what makes sense for the student in front of you.

6. Students ‘learn less’ in Project-Based Learning.

How true this is depends on the data you’re looking for, how you define ‘learning,’ and how willing you are to look at your own school and classroom as a way to kind of research lab that produces data so you can be ‘research-based.’

There are likely studies that say PBL ‘doesn’t work,’ which means that it’s been demonstrated that students can’t learn effectively through creating products or leading efforts for local acts of service through inquiry. Which means that study is absurd. Education needs better research, and the mixed results’ of PBL are a prime example of that.

What matters is the learning, not the purported research that merely predicts what leads to effective learning in universal contexts and applications that have little to do with your students in your classroom.

7. Project-Based Learning requires expensive technology.

No learning requires technology unless you’re learning about technology.

Using technology in project-based learning can certainly enhance its strengths and widen its scale—and even enable more precise personalization of the PBL teaching and learning process—but it’s by no means absolutely necessary, nor even should it be considered ‘less than’ without it.

What matters is the process, not the technology.

8. Myth: Project-Based Learning is less ‘rigorous’ than traditional academic work.

Put simply, PBL is inherently neither more nor less rigorous than ‘traditional academic work.’

You can assign Shakespeare and a six-page research paper in a multi-genre thematic unit to the result of significant complexity and rigor, and can create a fairly loose and simple-minded project that results in very little cognitive demand within their unique zone of proximal development—and in this case, it’d be true that the former is ‘more rigorous’ than the latter.

But you can also ask students to work with local water quality organizations to design and market community-based practices that lead to cleaner watersheds and, in general, an intact and robust native, water-based ecology–a project that could have research components, writing and literacy demands, expert technology use, extensive publishing, and more. (Not to mention that ‘rigor’ is one of the most misunderstood terms in education to begin with and isn’t itself inherently ‘good.’) Between ‘academic learning’ and ‘project-based learning,’ one isn’t any better or worse than the other.

Nor are they mutually exclusive.

See also Fill In The Blank Prompts To Help Students Design Their Own Projects.

9. Myth: The teacher always has to create a rubric.

Eh.

Between the teacher, the parents, the community, and the students themselves, the teacher is the expert in understanding. And, to a degree, process, resourcefulness, assessment, and so on. And if they’re experts in assessment and understanding, that understanding should be used by the student–to co-create a rubric, possibly. Or perhaps the teacher can connect the student with an expert or authentic audience to see what would make the ‘project’ ‘work.’

It’s may be possible that depending on the context, the teacher is the best person to create the rubric, but it doesn’t have to be the case.

10. Myth: Project-Based Learning makes classroom management more difficult.

Bad classroom management makes classroom management more difficult.

A lack of leadership in the school or district can make classroom management more difficult.

No clear behavior plan at the grade, team, or department level can make classroom management more difficult.

While it’s possible learning through projects could lead to challenges in the same, sit-and-get direct instruction and related ‘conventional’ approaches lead to classroom management problems of their own.

11. Myth: Project-Based Learning isn’t ‘research-based.’

False.

In short, we need better research in education. There is ‘research’ that supports ideas that have no business in a modern classroom, while a dearth of research on the kinds of ideas that could transform it but suffer (in the eyes of research pundits) as ‘not research-based.’

Do your own research in your own school or classroom–and invite those experts in to help.

12. Myth: Students must publish work to a ‘real world’ audience.

This myth about PBL isn’t hugely problematic because in general, it’s solid advice. (Which is why I included it so low on the list.)

Authenticity is a word often lobbed around spaces in education to describe ‘real world’ work, knowledge, or skills. This is actually a monumental concern (in my opinion, anyway) perhaps worth more scrutiny than the idea of PBL itself, but that’s another topic for another day.

For the purpose of this post, just consider that while authenticity is ‘good’ and ‘real-world audiences’ for student work and thinking can increase that authenticity, it can also complicate the projects and thus the learning process in a tangle of privacy issues, student safety, digital citizenship, and dozens of other related concerns.

While a catalyst for student engagement, project-based learning doesn’t absolutely have to end up ‘solving real-world problems’ (this is problem-based learning, place-based education). If the opportunity fits the student need, make it happen. If not, focus on the student and their needs rather than some artificial sense of progressiveness and innovation.

12 Myths About Project-Based Learning