What Are The Principles Of Sustainable Learning?

by Terry Heick

This post has been updated and republished

What would the opposite of the industrial learning model–the existing vision of most public education systems worldwide in the 21st century–look like?

It seemed to me that it might work something like a farm or garden or other ‘human-designed but nature-based model.’ The big idea of this post is using nature as a standard for learning, but it also then functions in juxtaposition to our existing model.

Put another way, it’s only because most existing learning models do not parallel natural patterns that this model would even be worth thinking about. Accordingly, considered several titles to this post, among them:

The Opposite Of Learning Factories: A Human Learning Model

How To De-Industrialize School: An Agrarian Learning Model

How To Design A School That Would Never Fail

If Schools Weren’t Factories: An Agrarian Learning Model

If Schools Were Small & Humble: An Agrarian Learning Model

But the idea of humility in learning seems to be at the root of it all. The concept of public education, for example, is only ‘bad’ insofar as it doesn’t accomplish its goals. If its purpose was merely to ‘to expose students to academic content,’ they’d be wildly successful. We could even get more specific–a possible goal being ‘to expose students to academic content in groups of 30,’ we’d still be doing exceptionally well.

We could even say the goal is to ‘group students by the dozens and ask them complete lessons designed by teachers in the content areas of math, science, social studies, and language arts for about an hour a day,’ and we’d still be enormously successful for the most part. Schools–and schooling–could be said to possess quality.

Things start to get murky, however, when we start getting specific and ambitious. We can’t just ‘expose’ students to content–we want them to ‘master’ it. Be ‘proficient’ or ‘distinguished.’ And not most content–all of it. And not most students–all of them. And not for the sake of knowledge, but ‘college and career-readiness.’

And so on.

These are our clearly stated goals and they don’t always make sense.

The Effect Of Ambition

Few things invite ambition more urgently than affection, and it is our affection for children that pushes us to create ambition for them. Curriculum, academic standards, grades, cut scores, progress/growth over time, and more all born out of love. The underlying assumption of any curriculum is that it is worthy of study, and the underlying assumption of school is that it is good for students, and if they ‘do well at it,’ they will have the ‘best chance for success’ in life.

That school and life couldn’t be more different is, hopefully, clear. One takeaway is that schools only fail relative to a goal; if we changed the goal, it changes the nature of any failure. Most challenges are challenges of scale, so I became curious here what ‘school’ would be like if it weren’t so ambitious: Not if we stopped wanting the best for children, but rather if designed a learning model that couldn’t fail by design because its goal was enduring quality based on place, limits, scale, affections, sustainability, adaptivity, and patience.

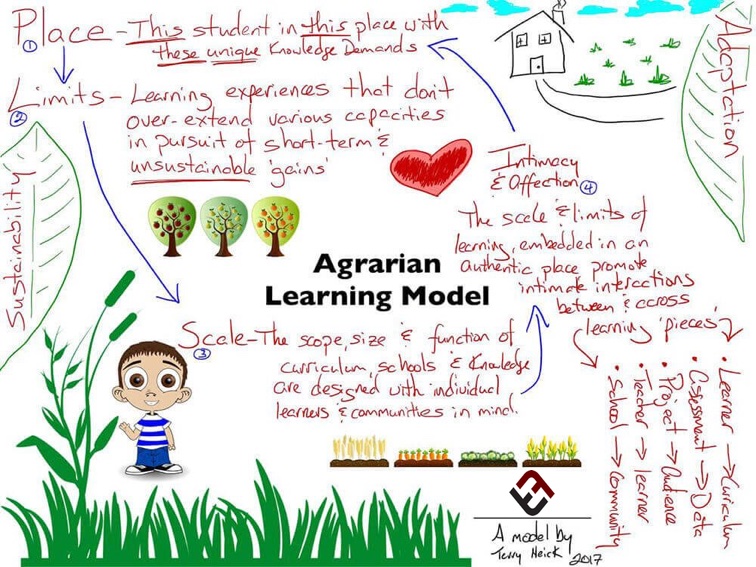

Designing The Perfect School: 7 Principles Of Sustainable Learning

1. Place

The idea: Learning is both embedded within and caused and effected/affected by a place native–and critical–to the learner

Every farmer works not a farm, but their farm–and it’s only a ‘farm’ at all as a matter of language, which is the process of taking something specific and making it universal for the purpose of communication. This is a kind of standardization.

The Agrarian Learning Model is not concerned with students, but this student in this place with these unique knowledge demands.

I wrote in Why Your Students Don’t Remember What You Teach: The Overwhelming Power Of ‘Place’ In Learning that, “A home, a yard, a park, a garden, a church, and any other physical location have embedded within them an impossibly complex history–one that is parallel to local cultural memory,” and suggested that a ‘locally-based, making curriculum’ might make sense in response. I also wrote, ‘Production apart from a place is industry; Production within a place is craft.’

A learning model designed well with a specific student and place in mind cannot fail. If it does fail, there is a failure in design or a blindness to the place and student.

2. Limits

The idea: Everything has natural limits and using and misusing places and ideas and people and communities is caused by either knowing or not knowing those limits

The soil precedes the farm, and thus supersedes any goals that farm may self-create. Put another way, the soil must remain healthy and so be properly used or the farm will fail. In the short-term, chemicals, fertilizers, and other means of gain may be used and even well-implemented, but the farmer–in intimate interaction with their soil on their land--is always aware of its limits and potential mistreatment.

The same applies to farm equipment, available daylight, growing seasons, and even the knowledge and skill of the farmer. To ignore these limits is to practice ignorance.

In a school or district, this would look like, among other things, learning experiences that don’t over-extend related capacities in pursuit of short-term & unsustainable ‘gains.’

A learning model created according to the natural limitations of its own bits and pieces can’t fail, or the design exceeded some/all limitations.

3. Scale

The idea: Because of limits, there is an appropriate scale that ‘things’–people, ideas, families, communities, corporations, technologies, etc.–work ‘well’ at and in

Closely related to the idea of limits is the idea of scale. No one would ever plant a garden so large that they couldn’t tend to and cultivate its crop–or they would only do so once, only to realize their own hubris and redesign the following year in light of their experience.

In the Agrarian Learning Model, the scope, size, and function of curriculum, schools & knowledge are designed with individual learners and communities in mind.

A learning model created with scale in mind can succeed only if the appropriate scale is selected–if the ambition of the curriculum aligns with the curiosity of the students, the ambition of the school matches the capacity of its pieces, etc.

See also The Inside-Out School

4. Intimacy & Affection

The idea: You can’t know ‘things’ but you can know each ‘thing’

To care about something requires us to understand it–the granular it rather than the larger categories we instinctively place them in

The gardener doesn’t plant a tomato plant but that tomato plant. A parent doesn’t parent a child but that child. Someone camping doesn’t choose a campsite but that small piece of land which then becomes, categorically, a ‘campsite.’ That is a matter of scale that enables intimacy and affection. (She is not a ‘student,’ she is Chelsea.)

While tending to the tomato plants, the gardener would notice problems with insects or exposed roots or eroding topsoil because the scale was such that she could, which would condition the gardener to look for these things, and develop an affection for them.

In the Agrarian Learning Mode, the scale and limits of learning, embedded in an authentic place, promote intimate interactions between and across…

learning and curriculum

assessment and data

project and audience

teacher and learner

learner and data

teacher and family

family and curriculum

curriculum and project

etc.

…you get the point.

A learning experience designed through intimacy and affection could not ‘fail’ or the intimacy wasn’t affectionate.

For a non-agrarian example, if a mother wanted to help her child learn to walk, she would likely do so with an intimate kind of affection in mind: She would know her child’s previous attempts at walking, how long ago they started to crawl, at what age siblings started walking, if the child showed ambition for walking, and so on.

With these factors in mind, she’d decide whether to let the child grip her thumbs or if she wanted to hold the child’s hands herself. She could decide if the child was ready to stagger back and forth between herself and a sibling, or still needed time in the walker because knew that child–and she knew that child because she had watched that child grow closely, which she had done because she loved the child.

5. Patient

The idea: Everything has its own time and pace and schedule

As the farmer has goals for his land, the school has goals for the students. The farmer, though, is patient–and not always because they’d want to be. Sometimes they may show patience out of wisdom, but it’s more likely that that wisdom is a product of the necessity of patience; They have no other choice. The corn, nurtured and grown with affection, will still do so on its own time. The soybean plant will bear what it can. The tractor will move as the tractor does.

The soybean plant will bear what it can. The tractor will move as the tractor does. In the Agrarian Learning Model, schools are patient. But more critically, students feel patience and can demonstrate it with and among themselves.

This isn’t apathy–true patience never loses sight of a goal or it’s not patience at all, but indifference. Acts of genius are rarely created out of compulsion. Patience yields opportunity for the playful interactions between student and ideas–and one another, where creativity can be born and intellectual affection and curiosity can thrive.

A learning model that is ‘patient’ can only fail relative to standardized and universal goals.

6. Sustainable

The idea: Learning has to be sustainable and knowing has to be sustainable and the parts we use–teachers, schedules, training, tools, schools, projects, and more–all must be equally sustainable

Back to nature and plants and crops–because the farmer must return to the same farm and the same soil, and knows which seasons are coming and what variability exists within those seasons, there is very little that farmer would do that’s wouldn’t be sustainable. For a farm to do anything well, it must be able to do so again as a matter of pattern and design.

The tangible (e.g., teachers, students, technology, buildings) and intangible (e.g., enthusiasm, curiosity, budget, affections) bits of education were all designed and used so as to not deplete themselves, but grow interdependently.

A learning model that is not sustainable by definition cannot be successful.

7. Adaptive

The idea: In quality ‘systems,’ one thing adapts to another. Nature is the archetype for this principle.

Just as the farmer must adapt to changing weather, crop demand, or local resources, in the Agrarian Learning Model everything would adapt to everything else–curriculum to local culture, assessment to student performance, Lexile levels to student reading levels, schedule to student needs, technology to changing budgets, etc.

A learning model that doesn’t adapt to the learners it’s designed for can only be successful insofar as allows learners to adhere to its form. If it adapts to the learner’s ability and curiosity and knowledge demands and pace, how can it fail? It can’t.

If Schools Were Small & Humble: An Agrarian Learning Model; Designing The Perfect School: 7 Principles Of Sustainable Learning